The Journal of Revolution and Liberation

"Resilience as Resistance"

Volume 2, Issue 3 (December 2019)

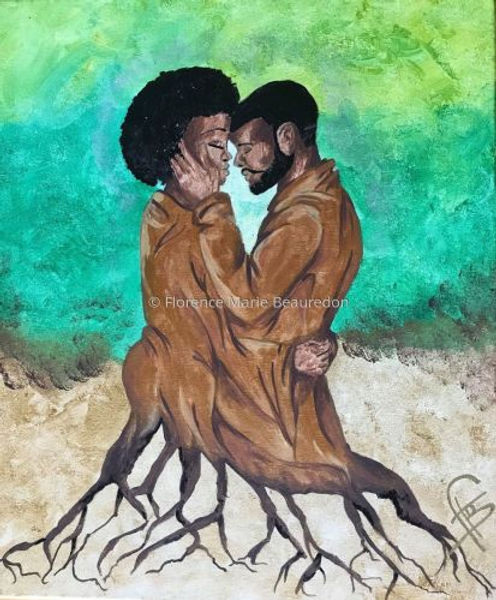

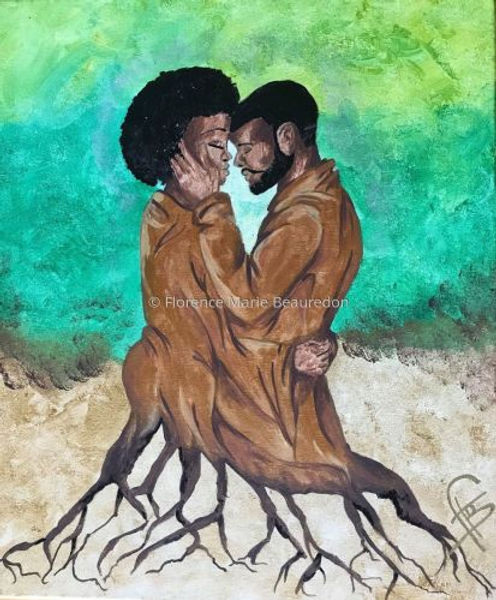

Cover Art: "Black Love Roots" by Florence Marie Beauredon

The Journal of Revolution and Liberation

Volume 2; Issue 3 (Dec 2019):

"Resilience as Resistance"

Table of Contents

1) JRevLib Vol. 2 No. 3 Editorial Summary: Resilience as Resistance

FLOW A: REMEMBRANCE

2) "Undaunted", by Arvis Mortimer

3) "Beware the Promise Today", by Errol Ross Brewster

FLOW B: DECIPHERING

4) "Word, Sound and Power: Decoding the Racialization of the English Language", by Dion Hanna

5) "Sacred Geometry", by Michael Pierre

FLOW C: RENAISSANCE

6) "Aquaculture: An Industry for Bahamians to Invest In", by Amina Moss

9) "Resilience: An Art Series", by Florence Beauredon

Editorial Summary: Resilience as Resistance

We diasporic Africans have traversed many waters since our continental origins. The Atlantic ocean swallowed many of the Ancestors while crossing during the Ma'afa (trans-Atlantic slave trade). And still to this day, these waters swallow African migrants en route to the West, desperate for the dream of a better life.

Hurricane Dorian came to the Bahamas, land of the shallow waters, and took hundreds of souls to the water. Many many of those hundreds, were people descended from survivors of the migration from Haiti to the Bahamas, a short but treacherous passage which has also swallowed many in search of opportunity. The Sea cries out!

But, the Hurricane also exposed heroism, community, ingenuity and above all the Power of Love. And this we must remember.

And of course, the Bahamas is not alone; Africans throughout the diaspora, and humans worldwide, are falling victim to dramatic environmental and climate shifts, leading to displacement, war, poverty and lack of security. Ironically enough, these are the result of the same global capitalist-imperialist ambitions and excesses that led to and sustained the Ma'afa. Hurricane capitalism came first, exploiting human beings, descrating the environment for naked profit margins drenched in blood. The Earth cries out!

But, if you are reading this, you have not been swallowed by the waters; you are a product of Survival. Therefore, with chest perpendicular to the sky- proud, brave, bold and resilient- there is little choice but to move forward, even as we remember those taken by the waters. Our only choice is to adapt and respond to challenges as they come. This is the human imperative and it is what we have always done to survive. And our determination to survive, in the context of the dehumanising conditions of capitalist-imperialism, is a form of Resistance.

We open this issue, "Resilience and Resistance" with 'Undaunted' by Arvis Mortimer, a poem about the Bahamian experience of Hurricane Dorian and the heroic response in the aftermath, framing the overall theme of this edition. This is followed by 'Beware the Promise Today', a photoessay by Errol Ross Brewster documenting the decay of the national railway in parallel to socioeconomic decay in the politically turbulent Guyana of the 1980s, and the resilience and innovation of its people even in the face of the stark inadequacies of the state.

In Dion Hanna's piece 'Word sound and power: decoding the racialisation of the English language' we see language deconstructed, as a tool of our survival in the context of a detrimental white supremacist construct. The key to the manifestation of our inherent ingenuity lies in deciphering the divine patterns of our existence, as beautifully referenced in Michael Pierre's 'Sacred Geometry'. The answer is at our feet.

For too long, we have not been drivers in our economic development and resilient solutions must be posed to confront global economic inequity. In the context of the Bahamas, Amina Moss proposes harnessing the industrial powers of the waters in 'Aquaculture: An industry the Bahamas should invest in'. Following this, Indira Martin outlines a case for cannabis as an economic equaliser and catalyst for biomedicine in the Caribbean in 'Modelling cannabis for excellence in biomedicine and equitable wealth distribution'. And as a continuation of this theme, we interview Francine Russell and Andrea Moultrie, co-founders of the Heritage Partners, a business based around the concept of Sankofa, or looking back to look forward.

Finally, we close out the issue with an art series by Florence Beauredon, highlighting the concept of 'Resilience as Resistance'. Our beautiful cover art, 'Black Love Roots', comes from this collection.

And so, armed with the Power of Love, and compelled by a History and Herstory of Survival, we press on to the Future.

"Steady sunward, though the weather hide the wide and treacherous shoal"

- excerpted from The Bahamas National Anthem

Undaunted

by Arvis Mortimer

Arvis is a public health specialist based in The Bahamas who greatly appreciates, and occasionally dabbles in, the Arts

Summary: I was inspired to write this piece immediately after Hurricane Dorian, the most catastrophic hurricane to ever make landfall in The Bahamas, left the archipelago. In its wake we witnessed unprecedented devastation and damage, along with the embodiment of the most noble human traits - such as resilience, strength, kindness and generosity - en masse. I found it important to capture this moment - and the way forward - in poetic form.

A tropical clime and ever warming seas

Beckoned hurricane Dorian

which razed two dynamic Bahamian communities.

Its highspeed winds with the colossal ocean swells

Destroyed homes, businesses, infrastructure and

Snuffed out numerous lives as well.

Yet in the midst of this unparalleled tragedy

Hope was inspired through many acts of

Love, perseverance, dedication and bravery.

People arose without prompt or cue

Helping and supporting one another

As the cyclopean storm subdued.

Now in the aftermath we must forge ahead

Our tasks at hand are to rescue, rebuild, restructure

and honor the dead.

We also have the opportunity to create something new

Since climate change is a reality

That the archipelago must adapt to.

The Bahamian spirit of fortitude will forever soar high

So let us confidently move forward, upward and onward together

With the end goal in sight.

Heads lifted up towards the rising sun

Collectively treading undaunted

Until the work is done.

Beware the Promise Today

by Errol Ross Brewster

Errol Brewster is a Caribbean artist from Guyana, living in the United States. With more than four decades of a Caribbean-wide, multimedia imaging practice, he has participated in multiple CARIFESTA’s; the EU’s Centro Cultural Cariforo, “Between the Lines”, travelling exhibition, 2000; the First International Triennial of Caribbean Art, 2010; and the Inter-American Development Bank’s “Sidewalks of the Americas” installation, 2018.

Summary:

“BEWARE THE PROMISE TODAY” is a photo essay about the demise in Guyana, in the early 1970s, of the very first trains to be introduced in all of South America in 1846, and the impact on the Guyanese people – in particular the poor and vulnerable, of a peculiar political culture that arose in that time and has continually plagued the country until now.

It is offered as symbolic caution, and a reminder of how the placing of party politics (The Paramountcy of the Party was a much touted doctrine of the ruling party at that time) above country led to ruin then, and could likely, without extreme vigilance, now and in the future, rob the country of its new found wealth. Included is a George Lamming quote, succinctly summing up the tone of the country in the period in which these photographs were made.

They were made in the early 1980s, on B&W film and solarised in the processing to lend them an air of menace, which was a hallmark of the time. One was much later computer manipulated to introduce colour for a different emotional impact. Very few of them have seen the light of day in the four decades since they were made.

The country, at the time, was in a very oppressive mode under a government so paranoid about its legitimacy (of which it had none) that it could not tolerate free speech. Journalists and photographers were routinely harassed and worked under seriously threatening circumstances. I was banned from the national archives; arrested and hauled off to the police station on occasions; suffered equipment seizures; intimidated by police and party thugs on the streets. And it grew so dire I had to have a body guard while photographing protests and disturbances in the city.

But I was lucky: Father Darke wasn’t. He was an elderly, expatriate, Jesuit priest, who was a photojournalist for the Catholic Standard newspaper and he was killed by party thugs in broad daylight as he covered a protest in front of the Magistrate Court in this same period. This is also the period in which Dr Walter Rodney was assassinated.

Click here for the full article: https://veerlepoupeye.wordpress.com/2019/10/24/errol-ross-brewster-beware-the-promise-today/?%20fbclid=IwAR0YmczaDKh6q9r42v5xh8Bj_B3GRV66pIk2Hf_531NuFnIOZMXwQhiRIV4

Word, Sound and Power: Decoding the Racialization of the English Language

by Arthur Dion Hanna Jr.

Dion Hanna is a Bahamian legal scholar, lecturer, researcher and community activist based in the UK

Summary: This article explores the social realities underpinning the language of race and its historical etymological congruence with and institutional structural operation as a substratum of the English language. We review the pervasive integral essence of hierarchy and subordination that is inherent to the spoken and written word in the structural linguistics of the English language. Of necessity, this is an essential historical and sociological exercise that engages the wider concern of constructs of race and identity in English society

“For last year's words belong to last year's language. And next year's words await another voice”[1]

“But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought”[2]‘

When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.’

’The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’

’The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master — that’s all.”[3]

“Writers are obliged, at some point, to understand that they are involved in a language which they must change. And for a Black writer in this country to be born in the English language is to understand that the assumptions on which the language operates are his enemy. For examples, when Othello accuses Desdemona, he says he ‘threw a pearl away richer than all his tribe’. I was very young when I read that and I wondered ‘richer than all his tribe?’. I was forced to reconsider similes: as black as sin, as black as night and blackhearted”[5]

This article explores the social realities underpinning the language of race and its historical etymological congruence with and institutional structural operation as a substratum of the English language. We review the pervasive integral essence of hierarchy and subordination that is inherent to the spoken and written word in the structural linguistics of the English language. Of necessity, this is an essential historical and sociological exercise that engages the wider concern of constructs of race and identity in English society.

Christine Mallinson points out that language is “fundamentally at work” in how we operate as individuals, as members of various communities and within cultures and societies. She indicates that as speakers, we learn not only the structure of a given language; we also learn cultural and social norms about how to use language and what content to communicate.[6] In this regard, it has been indicated that “standard language ideologies” can result from and contribute to ideologies about race, ethnicity and nationalism as well as contributing to “ideologies of prescriptivism, tinged with racism and xenophobia”.[7] In this respect the concept of race has been integral as to how languages have been “defined” over time, with language being central to the theorization and expression of race in western scholarship.[8] As such, it has been asserted that current ways of talking about race are the “residue” or “detritus” of earlier ways of talking about race and are the “pale reflection of a more full bodied race discourse that flourished in the last century”.[9] This underscores the assertion that, given that racial prejudice is an unnatural and learned phenomenon, the attempt to understand the “mechanisms through which literature shapes and is shaped” by it is an important one.[10]

However, as pointed out by Hudley, conflicting models of racial classification have been utilized in linguistics, with linguists failing to develop a “cohesive theory or model of race”.[11] In this context, this is compounded by the fact that there has been minimal formal discussion about race, particularly in the United States but also in the United Kingdom, due primarily to the under-representation of Black and ethnic minority scholars.[12] However, it has been contended that the relationship between race, language and racism plays a “key role” in reflecting and defining the manner in which human societies are structured and is deserving of study as a separate field described as “raciolinguistics”.[13] In this regard, it has been indicated that some linguists study race in a vacuum without theorizing race at all but that race scholars who do think about race a lot often neglect the “central role” that languages play in the processes of “racialization”.[14] In this respect, it has been pointed out that language is often overlooked as one of the most important cultural means that enables people to distinguish themselves from others but that, rather than being fixed and predetermined, racial identities can shift across contexts and even in moment to moment interactions, with race being both a social construct and an important social reality.[15] This amoeba like intersectional nature of racism is enhanced by constant interaction with other social phenomena such as gender and class and results in hybrid manifestations often ignored or unobserved by Western academia.[16] As indicated by Judith Baxter, reciprocally, identities are constructed by and through language but also produce and reproduce “innovative forms of language”.[17]

This confirms Foucault’s assertion that language as a system does not represent human experience in a transparent and neutral way but always exists within “historically specific discourses” and that these discourses are often competing, offering “alternative versions of reality”, serving different and conflicting power interests.[18] He indicates that such interests usually reside within “largescale institutional systems” such as law, justice, government, the media, education and the family, with a range of institutional discourses providing the network by which “dominant forms of social knowledge are produced, reinforced, contested or resisted”.[19] This underscores the fact that contemporary discourse is littered with “confused and contradictory meanings” regarding race and racism.[20]

It has been pointed out that critical to the understanding that race is a social construction is the recognition that language must play a strong role in assigning “racial meaning to bodies”,[21] which has inspired studies of language ideologies that pay careful attention to race,[22] often occurring through “covert racializing discourses” that do not explicitly mention race[23] but work to produce “whiteness and the privileged place of whites within racial hierarchies”.[24] In this regard, it has been indicated that race and ethnic perception are “intertwined” and depend largely on the “historical and geographical context” and the “specific community discourse” that has emerged out of this context.[25]

However, it is important to consider that race, ethnicity and language are “products of colonial distinctions”, with ideas about language coming from “profound sites of reproduction of inequality”.[26] In this transnational frame of reference, the modern world is “profoundly shaped” by the globalization of European colonialism, with a continual re-articulation of colonial distinctions between Europeanness and non-Europeanness and “by extension, whiteness and non-whiteness”, with these distinctions anchoring the “joint institutional reproduction of categories of race and language”, as well as “perceptions and experiences thereof”.[27] This “coloniality of language” is a process of racialization of colonized populations as “communicative agents” beginning in the 16th century and continuing until today.[28]

In this respect, it has been pointed out that contemporary raciolinguistic ideologies must be situated within colonial histories that have shaped the “co-naturalization of language and race as part of the project of Modernity”.[29] It has been indicated that this is critically important because the construction of race was an “integral element of the European national and colonial project” that discursively produced racial Others in opposition to the “superior European bourgeois subject”,[30] with this positioning of Europeanness as superior to non-Europeanness being part of a “broader process of national-state/colonial governmentality”[31], a form of “governmental racialization” that imposed European “epistemological and institutional authority” on colonized populations worldwide as a justification for European colonialism.[32] In this regard, this ideology was defined by a process of “othering” in which the colonized were portrayed as “primitive, backward and savage”, validating their enslavement and disempowerment. In a British context, the colonized other was placed:

“in their otherness, their marginality by the nature of the 'English eye', the all encompassing 'English eye'....The 'English eye' sees everything else but is not so good at recognizing that it is itself looking at something. It becomes coterminus with sight itself. It is, of course, a structured representation nevertheless and it is a cultural representation which is always binary. That is to say, it is strongly centered; knowing where it is, what it is, it places everything else. And the thing which is wonderful about English identity is that it didn't only place the colonized Other, it placed everybody else”.[33]

In a socio-cultural frame of reference, Stuart Hall points out that Black people are “typically” the objects but “rarely” the subjects of the practices of representation. He further indicates that the “struggle” to come into representation was predicated on a critique of the degree of “fetishization, objectification and negative figuration” which are so much a “feature of the representation of the Black subject”.[34] This was perpetuated through popular culture and “imprinted in everyday imagery”, as demonstrated in a Pear's Soap advertisement from 1899 in which Pear's Soap was described as being a “potent factor in brightening the dark corners of the earth as civilization advances”, demonstrating the manner in which imagery is a powerful force in perpetuating ideas of “everyday racism”.[35]

However, it has been asserted that the utilization of “semantic somersaults”, with the substitution of the terms “race” for “racism”, was crucial into the transformation of the “act of a subject into an attribute of an object”, with “the neutral shibboleths of difference and diversity” replacing terms such as “slavery, injustice, oppression, and exploitation.” In this context, the “scientifically incoherent concept of race” becomes real through “speech acts” which serve to stabilize race as a reality rather than denaturalize it as a social construction.[36] Glickman points out that:

“Something similar is at work in the use of euphemisms which suggest that race is a fact—something that can be highlighted in a neutral way—rather than an ideology, a tool of oppression”.[37]

This ensures that we are confronted with “dysfunctional racial discourse” that doesn’t always mean what it says and seldom says what it means.[38] This underscores the assertion that contemporary discourse is “littered” with “confused and contradictory” meanings regarding race and racism.[39] In this regard, Omi points out that, while rejecting biological notions of race, we need to “vigorously assert” the importance of social constructs of race in individual and institutional life. He indicates that this does not mean that we can have an “accurate, precise, or scientific form of racial classification”, as racial categories dramatically change over time and are the result of “distinct political claims for recognition”, resulting from a “complex negotiation between the state and group/individual identities”.[40]

He indicates that the problems of “conceptual inflation and its political consequences” are of real concern, with the term "racism" in popular

political discourse being increasingly subject to “conceptual deflation” and that what is considered racist is being narrowly defined in ways that

“obscure rather than reveal the pervasiveness of racialized power” in the

social order.[41] In this regard, he points out that the reduction of racism to hate, both conceptually and politically, limits our understanding of racism and the ways we can challenge it and that racism has been silently transformed in the “popular consciousness” into acts that are “abnormal, unusual, and irrational – crimes of passion”. He asserts that missing from all this are the “ideologies and practices” in a variety of sites in our society that reproduce racial inequality and domination.[42]

In this frame of reference, the White western academic world has primacy in creating and engaging the language of race, with non-White European peoples being defined rather than defining themselves, which emphasizes the reality that the phenomena of race and racisms are exclusively the constructs of the White western world.[43] In this context, “bottom up social relations” are mirrored in “top down systems of categorization”.[44]

Rosa points out that any racialized group can be “linguistically stigmatized” with ideologies of “language standardization and languagelessness”. Even if a group is not yet racialized, it could become racialized through these ideological and institutional processes.[45] This demonstrates the reality that racism is more than structure and ideology but is a process that is “routinely created and reinforced through everyday practices” as indicated in Philomena Essed's formulation of the concept of everyday racism, which connects “structural forces of racism” with routine situations in everyday life, linking “ideological dimensions of racism” with “daily attitudes” and interpreting the “reproduction of racism in terms of the experience in everyday life”.[46]

In this socio-cultural landscape, driven by cognitive dissonance, race discourse is constrained by many in the White western cosmos because many are afraid to be accused of racism.[47] This is a natural consequence of a “pathology of imperial guilt” which is an “intellectual paralysis” which accompanies a historical process of “earnest critical reflection” on “collective sins of the past”. This historical amnesia[48] perpetuates a “series of false binaries”, which prevents the “lessons of human destruction within the colonial West” from informing a broader understanding of of the “causal relationship” between the depravation of rights and genocide.[49] In this regard it has been indicated that:

“The recognition of collective responsibility for the historical tragedies of colonialism, slavery, capitalist exploitation, and imperial war makes it difficult for Western critics of human rights to acknowledge the full implications of a simultaneous legacy of “liberalism, social democracy, labor agitation, feminism, gay rights advocacy, and anti-racism that [also] characterize much of the social history of the West in the last two centuries”.[50]

In this sea of obfuscation engendered by Western cognitive dissonance and historical amnesia, racism thrives deeply entrenched in the structural and institutional fabric of Western polity impacting on the daily lived experiences of Black peoples placing them on the margins of social existence. This confirms Amilcar Cabral's indication that in combating racism we do not make progress if we combat the people themselves and that we have to “combat the causes of racism”. He points out that If a bandit comes to a house and you have a gun, “you cannot shoot the shadow of the bandit but have to shoot the bandit”. This results in many people losing energy and effort, and making sacrifices combating shadows. He concludes that we have to “combat the material reality that produces the shadow”.[51] In this regard, Toni Morrison contends that:

“Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity-driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek – it must be rejected, altered and exposed. It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind. Sexist language, racist language, theistic language ― all are typical of the policing languages of mastery, and cannot, do not permit new knowledge or encourage the mutual exchange of ideas”.[52]

Ryuoko Kubota argues that the ethics promoted by black feminism emphasizes a “personal ethical commitment” to anti-racism and that “Epistemological anti-racism” invites scholars to validate alternative theories, rethink citation practices, and develop “critical reflexivity and accountability”.[53] In this context, it has been pointed out that there is a need for more “critical and sophisticated” reading of the “so called post racial world” to reassert very strongly the central place of race and anti-racist practice in “contemporary social formations”.[54] In this respect, working within an “anti-racism framework” involves the use of language that does not “stigmatize or reproduce oppressive forms of power”.[55] This emphasizes the “centrality of language” in the discourse of anti-racism and the need for meaningful change through the “poetics of words and action” giving voice to the “possibilities of change”.[56]

Further, Rosa contends that:

“In order to disrupt the linguistic reproduction of radicalization and socio-economic stratification, we must move beyond asserting the legitimacy of stigmatized language practices,”....focusing instead on interrogating the societal reproduction of listening subject positions that continually perceive deficiency. By changing our analytical strategy in this way, we can gain new insights into how the joint ideological construction of race, class and language perpetuates inequality.”[57]

As Helen Chapman points out, in the same way that the impact of art and design was used in the Victorian era to promote racial prejudice, “artistic outputs” can be used to counter racial prejudice, with imagery having a strong impact on “the way we see and think about things”, underscoring the need to keep producing positive imagery to “make racial prejudice history”.[58] In the battle against racism, oppression and discrimination, words are indeed potent weapons for social change and in the linguistic contestation with the racialist discourse inherent in the English language and in personal, structural and institutional manifestations of racism which permeate Western society. The critical importance of the transformative essence of language in the arsenal of anti-racist pedagogy cannot be overemphasized. Paramahansa Yogananda asserts that:

“Words saturated with sincerity, conviction, faith, and intuition are like highly explosive vibration bombs, which, when set off, shatter the rocks of difficulties and create the change desired”.[59]

In this regard, Yehuda Berg states that:

“Words are singularly the most powerful force available to humanity. We can choose to use this force constructively with words of encouragement, or destructively using words of despair. Words have energy and power with the ability to help, to heal, to hinder, to hurt, to harm, to humiliate and to humble”.[60]

As intoned by Ptah Hotep (Imhotep) in ancient Kemet (Egypt):

“Be a craftsman in speech that thou mayest be strong, for the strength of one is the tongue, and speech is mightier than all fighting”.[61]

There can be no doubt that there is a profound urgent need to grasp this concept of “word, sound and power” in the ongoing struggle for justice and equality. Left to its own devices, race and racism will continue to be embellished in linguistic oblivion and to remain a source of inequality, disempowerment and underdevelopment. This is a crucial concern. Indeed it is imperative that those engaged in anti-racism utilize language as a weapon in this battle against the unholy alliance of racism and linguistics which have been central to the invention and persistence of the phenomenon of racism and prejudice in all its manifestations. To paraphrase Nelson Mandela and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King jr, this anti-racist struggle has reached a “decisive moment”. We no longer have the luxury of waiting to begin to more effectively confront racism at every level. “Now is the time to intensify the struggle on all fronts”, hewing out of the “mountain of despair”, rooted in over 500 years of disempowerment, underdevelopment and marginalization, “a stone of hope” for a society built on a bedrock or equality of opportunity and social justice for all.[62] This is an essential imperative, given the pervasive and invasive nature of the ethos of “othering” of non-White peoples in Western societies, because, in the words of Ossie Davis, “struggle is strengthening” and “battling with evil gives us power to battle evil even more”.[63] Fanon anticipates this struggle when he advised us not to imitate Europe but to “combine our muscles and our brains in a new direction”, creating the whole man, whom Europe has been “incapable of bringing to triumphant birth”.[64] This was echoed by Malcolm X at the founding rally of the Organization of African American Unity some time ago:

“A race of people is like an individual man; until it uses its own talent, takes pride in its own history, expresses its own culture, affirms its own selfhood, it can never fulfil itself”.[65]

In this regard, Angela Davis contends that “as our struggles mature”, they produce “new ideas, new issues,and new terrains” on which we engage in the quest for freedom and that like Nelson Mandela, “we must be willing to embrace the long walk toward freedom”.[66] Shoffner points out that it is insufficient to only tell your children that “racism and racists are bad” and that, in a “world filled with empty rhetoric”, our children don’t need to hear words from us without action.

They need to see us “embody the beliefs we claim to hold dear”.[67]

As declared by His Imperial Majesty, Emperor Haile Selassie:

“Until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned: That until there are no longer first-class and second class citizens of any nation; That until the color of a man’s skin is of no more significance than the color of his eyes; That until the basic human rights are equally guaranteed to all without regard to race; That until that day, the dream of lasting peace and world citizenship and the rule of international morality will remain but a fleeting illusion, to be pursued but never attained”.[68]

Word Sound and Power!

A Luta Continua!

Free the Land!

References

[1] T. S. Eliot (197): Four Quartets Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston

2] George Orwell (2000): Nineteen Eighty Four by George Orwell. Penguin Books, London

[3] Lewis Carroll and Hugh Haughton (2012): Alice in Wonderland; and Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There. Penguin Classics, London

[4] Malcolm X (1965): Speech at Ford Auditorium. Available online <https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1965-malcolm-x-speech-ford-auditorium/>

[5] James Baldwin (1979): On Language, Race and the Black Writer. Los Angeles Times. Available online < http://marktwainstudies.com/brutal-things-must-be-said-james-baldwin-on-huckleberry-finn/>

[6] Christine Mallinson (2018): “Sociolinguistics” In Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Linguistics. Available online

[7] T. P. Bonfiglio (2002): Race and the Rise of Standard American. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin; (2012): “The Invention of the Native Speaker – Thomas Paul Bonfligio” In Multilingual 2.07

[8] Anne H. Charity Hudley, Christine Mallinson and Mary Buckholtz et. Al. (2018): “Linguistics and Race: An Interdisciplinary Approach Towards an LSA Statement on Race” In Proc. Ling. Soc. Amer. 3.8:1-14

[9] K. Anthony Appiah (1994): “Race, Culture, Identity: Misunderstood Connections”. The Tanner Lectures on Human Values Delivered at University of California at San Diego, October 27 and 28

[10] Lidija Hass (2017): “The Origin of the Other by Toni Morrison Review – The Language of Race and Racism” In The Guardian 18 October

[11] Anne H. Charity Hudley (2017): “Language and Racialization” In Ofelia Garcia, Nelson Flores and Massimiliano Spotti (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Language and Society. Oxford University Press, New York; Anne H. Charity Hudley, Christine Mallinson and Mary Buckholtz et. Al. (2018) supra.

[12] Anne H. Charity Hudley, Christine Mallinson and Mary Buckholtz et. Al. (2018) supra.

[13] Samy Alim, John R. Rickford and Arnetha F. Ball (2016): Raciolinguistics. Oxford University Press, New York

[14] Alex Shashkevich (2016): “Stanford Experts Highlight the Link Between Language and Race in New Book” In the Stanford News December 27

[15] Samy Alim, John R. Rickford and Arnetha F. Ball (2016) supra.; Alex Shashkevich (2016) supra.

[16] Arthur Dion Hanna jr (2011): Land and Freedom: Sabbatical Essays From a Legal Aid Lawyer. Karadira Blackstar, Nassau Bahamas;

[17] Judith Baxter (2016): “Positioning Language and Identity” In Sian Preece (ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Race and Identity. Available online <https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315669816.ch2>

[18] M. Foucault (1984): “What is Enlightenment?” In P. Rabinow (ed.) The Foucault Reader. Penguin, London

[19] Ibid.

[20] Michael Omi (2001): “Rethinking the Language of Race and Racism” In Asian American Law Journal, Vol. 8 (7)

[21] H. Samy Alim, John R. Rickford and Arnetha F. Ball (eds.) (2016) supra.; Jennifer Roth-Gordon and Jessica Ray (2018): “Language and Race” In Oxford Bibliographies February 22. Available online <https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199766567/obo-9780199766567-0183.xml>

[22] Elaine W. Chun and Adrienne Lo (2016): “Language and Racialization” In The Routledge Handbook of Linguistic Anthropology, Volume 21 (1); Jennifer Roth-Gordon and Jessica Ray (2018) supra.

[23] Hillary Parsons Dick and Kristina Wirtz (2011): “Racializing Discourses” In Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, Volume 21 (1); Jennifer Roth-Gordon and Jessica Ray (2018) supra.

[24] Jane H. Hill (2008): The Everyday Language of White Racism. Wiley-Blackwell, Malden MA; Jennifer Roth-Gordon and Jessica Ray (2018) supra.

[25] Anna-Lena Halloun (2017): “No, You're Just Half: The Impact of Everyday Racism on Mixed Race Identities in Belgium” In the Matheo WebBlog. Available online: <https://matheo.uliege.be/handle/2268.2/2546 >

[26] Erin (2018): “The Link Between Race and Language: Looking Like a Language – Sounding Like a Race” In the West Georgian, March 30. Available online <thewestgeorgian.com/the-link-between-race-and-language-looking-like-a-language-sounding-like-a-race/>

[27] Jonathan Rosa and Nelson Flores (2019): “Unsettling Race and language: Toward Raciolinguistic Perspective” In Language in Society, Vol. 46, 621-647

[28] Gabriela A. Veronelli (2015): “The Coloniality of Language: Race, Expressivity, Power and the Darker Side of Modernity” In Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women's & Gender Studies, Summer, Volume 13

[29] Jonathan Rosa and Nelson Flores (2019) supra.

[30] Ann Laura Stoller (1995): Race and the Education of Desire: Foucault’s History of Sexuality and the Colonial Order of Things. Duke University Press, Durham, N.C.; Jonathan Rosa and Nelson Flores (2019) supra.

[31] Nelson Flores (2013): “Silencing the Subaltern: Nation State Colonial Govermentality and Bilingual Education in the United States”. In Critical Inquiry in Language Studies Volume 10; Jonathan Rosa and Nelson Flores (2019) supra.

[32] Barnor Hesse (2007): “Racialized Modernity: An Analytics of White Mythologies” In Ethnic and racial Studies, Volume 30; Jonathan Rosa and Nelson Flores (2019) supra.

[33] Stuart Hall (1997): “The Local and the Global: Globalization and Ethnicity” In Anthony D. King (ed.) Culture, Globalization and the World System: Contemporary Conditions for the Representation of Identity. University of Minnesota Press

[34] Stuart Hall (1988): “New Ethnicities” In Kobena Mercer (ed.) Black Film, British Cinema. ICA Documents, Volume 7. ICA Publications, London

[35] Helen Chapman (2014): “Everyday Racism” In Manchester Historian, May 20. Available online <http://manchesterhistorian.com/2014/everyday-racism/ >

[36] Lawrence B. Glickman (2018): “The Racist Politics of the English Language” In The Boston Review, November 26. Available online <http://bostonreview.net/race/lawrence-glickman-racially-tinged>

[37] Ibid.

[38] Keith Woods (2002): “The Language of Race” In the Poynter WebBlog, August 25. Available online <https://www.poynter.org/archive/2002/the-language-of-race/>

[39] Michael Omi (2001): “Rethinking the Language of Race and Racism” In Asian Law Journal, Volume 8

[40] Michael Omi (1997): “Racial Identity and the State: The Dilemmas of Classification” In The Law and Inequality Journal, Volume 15; (2001) supra.

[41] Michael Omi (2001) supra.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Robert V. Guthrie (2004): Even the Rat Was White: A Historical View of Psychology. Boston, Allyn Bacon; John R. Rickford (2014): Increasing the Representation of Under-Represented Ethnic Minorities in Linguistics. Paper Presented as part of the Symposium : Diversity in Linguistics at the Linguistic Society of America Annual Meeting, Minneapolis, Minnesota, January 2014; Linguistic Society of America (2015): Annual Report: The State of Linguistics in Higher Education. Available Online: <https://www.linguisticsociety.org/resource/state-linguistics-higher-education-annualreport>; Dion Hanna (2018): “Cognitive Dissonance and Historical Amnesia: Racism and Race in a Bahamian Context” In Journal of Revolution and Liberation, Volume 1 (3), October. Available online: <https://www.jrevlib.org/vol-1-issue-3-2018>

[44] Jennifer S. Horschild and V. Weaver (2007): “Policies of Racial Classification and the Politics of Racial Inequality”. In Joe Soss, Jacob Hacker and Suzanne Mettler (eds.) Remaking America: Democracy and Public Policy in an Age of Inequality. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

[45] Jonathan Rosa (2018): Looking Like a Language – Sounding Like a Race: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and the Learning of Latinidad. Oxford University Press, New York

[46] Philomena Essed (1991): Everyday Racism. Sage Publications, London

[47] Ben Pitcher (2014): Consuming Race. Routledge, London and New York; Dion Hanna (2018) supra.

[48] Matt Broomfield (2017): “Britons Suffer Historical Amnesia Over Atrocities of Their Former Empire”. In the Independent Sunday March 5

[49] Rhonda E. Howard-Hassman: “Historical Amnesia, Genocide and the Rejection of Universal Human Rights”. In Mark Goodale (2014): Human Rights at the Crossroads. In Oxford Scholarship Online. Available online: <https://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199376414.001.0001/acprof-9780199376414-chapter-13 >

[50] Ibid.

[51] Amilcar Cabral (1973): Return to the Source: Selected Speeches of Amilcar Cabral. Monthly Review Press, New York

[52] Toni Morrison (1993): “Nobel Lecture”. On the Nobel Prize Website. Available online: <https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1993/morrison/lecture/ >

[53] Ryuoko Kubota (2019): “Confronting Epistemological Racism, Decolonizing Scholarly Knowledge: Race and Gender in Applied Linguistics”. In Applied Linguistics amz033. Available online: <https://academic.oup.com/applij/article/doi/10.1093/applin/amz033/5519375/>

[54] George J. Sefa Dei (2013): “Chapter One: Reframing Critical Anti-racist Theory (CART) for Contemporary Times”. In Contemporary Issues in the Sociology of Race and Ethnicity: A Critical Reader. Volume 445

[55] J. Hopton (1997): “Anti-Discriminatory Practice and Anti-Oppressive Practice”. In Critical Social Policy, Volume 17; G. Larson (2008): “Anti-Oppressive Practice in Mental Health”. In Journal of Progressive Human Services, Volume 19 (1); Simon Corneau and Vicky Stergioppoulos (2012): “More Than Being Against it: Anti-Racism and Anti-Oppression in Mental Health Services”. In Transcultural Psychiatry, Volume 49 (2)

[56] Nuzhat Amin, George Dei and Meredith Lordon (eds.) (2006): The Poetics of Anti-Racism. Fernonwood Pub., Halifax, Nova Scotia

[57] Jonathan Rosa (2018) supra.

[58] Helen Chapman (2014) supra.

[59] Paramahansa Yogananda (2012): “Paramahansa Yogananda on the Power of Affirmation”. In the Self Realization Fellowship E-Newsletter, July-August

[60] Yehuda Berg (2011): “The Power of Words”. On the HuffPost Web Blog, November 17. Available online: <https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-power-of-words_1_b_716183>

[61] Brian Brown (ed.) (2005): The Wisdom of the Egyptians: The Story of the Egyptians, the Religion of the Ancient Egyptians, the Ptahhotep and the Ke'gemini, the Book of the Dead, the Wisdom of Hermes Trismagistos, Egyptian Music, the Book of Toth. University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan

[62] Martin Luther King jr. (1963): I Have a Dream: Speech by the Reverend Martin Luther King jr. at the March on Washington. Available online <https://www.archives.gov/files/press/exhibits/dream-speech.pdf> ; Nelson Mandela (1990): “On Release From Prison, Cape Town, South Africa, 11 February”. In Nelson Mandela Foundation, Speaking Out for Justice: Key Statements and Speeches by Nelson Mandela, 1961-2008. Available online <https://www.un.org/en/events/mandeladay/legacy.shtml>

[63] Ossie Davis (2013): “Quote of the Week” In the Austin Daily News, July 16. Available online: <https://www.austinweeklynews.com/News/Articles/7-16-2013/Quote-of-the-week/ >

[64] Franz Fanon (1967): The Wretched of the Earth. Penguin, Harmondsworth

[65] Malcolm X (1964): Malcolm X's Speech at the Founding Rally of the Organization of African American Unity. Available online <https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/speeches-african-american-history/1964-malcolm-x-s-speech-founding-rally-organization-afro-american-unity/>

[66] Angela Davis (2016): Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine and the Foundations of a Movement. Haymarket Books, Chicago

[67] Bellamy Shoffner (2018): “If We Don't Hold the Line, Who will?” In Alexa Bigwarfe , Nancy Cavillones and Maria Desmondi (eds.) Lose the Cape: The Mom's Guide to Becoming Socially and Politically Engaged (& Raising Tiny Activists. Kate Biggie Press, USA (Kindle Edition)

[68] His Imperial Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie I (1963): Selassie's Address to the United Nations, 1963. Available online: <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Haile_Selassie%27s_address_to_the_United_Nations,_1963>

Sacred Geometry

by Michael Pierre

Michael is an artist from Trinidad and Tobago who recently gained an interest in Sacred Geometry.

Summary: Sacred Geometry reflects my belief that God created all with intentional design, which can be symbolised geometrically. The seed of life is one such representation. One of the meanings which inspired the piece is that the seed of life represents each day of creation - that is seven days translates into seven rings. The seed of life is the birth of all. This piece does not portray the seed of life perfectly; the intention behind it is to illustrate the birth of the creation of the seed. The woman again plays on creation. MA-ternal translate into MA-terial and MA-tter. The female light brings forth new life.

Sacred Geometry

Aquaculture: An Industry for Bahamians to Invest In

by Amina Moss

Amina has a doctorate in aquaculture. Her research focused on studying the effects of mollusks’ wastes (visceral organs, shells) as feed ingredients for marine shrimps and fish.

Summary: This is a brief introductory essay written in hopes of motivating Bahamians to look at aquaculture as a possible source of income, on the path to creating a self-sustainable Bahamas.

Seafood, just like fruits and vegetables, now need to be farmed in order to continue meeting the market demand (1). There used to be a time when this was not the case, Bahamians of a certain age constantly recall walking a few feet into the water and seeing a myriad of lobsters and conchs. However, the current state of fisheries in the Bahamas is such that fishermen have to go further out to get a decent catch (2). The reason for this is simple, marine resources are slowly but steadily being depleted from Bahamian waters due to overfishing, poaching, destruction of marine organisms’ natural habitats, and illegal fishing practices. A viable solution to our fisheries crisis is aquaculture (1).

Aquaculture is defined as the rearing, feeding, breeding and harvesting of marine and/or freshwater plants or animals in a controlled environment, such as a pond, in the ocean or in tanks (3). The benefits of aquaculture include food production but most importantly, restoring endangered species. Aquaculture may also generate a new source of income that is not entirely dependent on tourism, which employs the majority of The Bahamas’ workforce. Currently, more than 100 million people benefit from aquaculture to support their livelihood, all over the world (1). Many developing countries profit greatly from fish and shrimp farmers who grow their species in small plots of lands or offshore. This allows their citizens to obtain fresh, disease-free cultured products that are delicious and available all year-round even during their closed seasons as aquaculture products are usually unaffected by the restrictions placed on fisheries. A common example of fish being reared that have become safe due to aquaculture is the pufferfish (4). This fish has the ability to accumulate large amounts of tetrodotoxin in its liver, which can be fatal to the consumer. The buildup of this toxin, which is caused by them ingesting organisms such as crustaceans, gastropods and starfishes, can be avoided by controlling the diets of the fish. This is revolutionizing the pufferfish industry in Japan and it allows consumers to buy the fish with the assurance that the fish has now been rendered harmless. To have a successful aquaculture business, it is important to be able to monitor water and feed quality and a failure of which could be quite costly. A great selling point for aquaculture in The Bahamas is the fact that there is clear, pristine waters and should a serious investment in sustainable aquaculture be made, the country will be able to salvage its dwindling stock of groupers, spiny lobsters and conchs (2).

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 30% of the fish stocks that we depend on to get our protein are being captured at a “biologically unsustainable level” (1). Aquaculture has become a necessity to protect endangered species. Furthermore, compared to the rearing of pigs, cows and chicken, aquaculture produces less greenhouse gas emissions and requires much less feed. For example, it takes 6lbs of feed (dry weight) for beef cattle to gain 1lb while for fish and shrimps, the ratios vary between 1:1 to 2:1 (5, 6). By 2030, it is estimated that 62% of all consumed fish worldwide will be products of aquaculture, it is a growing industry that has a global market value of $203 billion (1). There is great potential in exploring aquaculture as a business venture for Bahamians.

It is important to note that aquaculture is not to replace fishing but rather to supplement it. While environmental factors such as hurricanes and global warming may be deterrents, there are many ways that countries have been able to construct ecologically friendly, strong structures (1, 7). Also, with the technology available, people are able to predict with incredible accuracy the changes in water temperatures, and they are able to monitor their cultured species underwater with the use of cameras, especially useful for species being grown in cages offshore. There are many aspects of aquaculture that have adapted with the times to make it a lucrative industry, all it needs is people to invest their time and money into it.

References:

1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Opportunities and Challenges. 2014. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

2. Sherman, KD, Shultz, AD, Dahlgren, CP, et al. Contemporary and emerging fisheries in The Bahamas—Conservation and management challenges, achievements and future directions. Fish Manag Ecol. 2018; 25: 319– 331. https://doi.org/10.1111/fme.12299

3. FAO. Definition of aquaculture, Seventh Session of the IPFC Working Party of Expects on Aquaculture, IPFC/WPA/WPZ. 1988; 1-3, RAPA/FAO, Bangkok.

4. Noguchi, T, Takatani, T and Arakawa, O. Toxicity of puffer fish cultured in the netcages. Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2004; 45: 146-149.

5. Shike, DW. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Driftless Region Beef Conference. 2013. Beef Cattle Feed Efficiency

6. Moss, AS, Koshio, S, Ishikawa, M, et al. Replacement of squid and krill meal by snail meal (Buccinum striatissimum) in practical diets for juvenile of kuruma shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus). Aquac Res. 2018; 49: 3097– 3106. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.13772

7. Waite, R, Beveridge M, Brummett R, et al. Improving productivity and environmental performance of aquaculture. Working Paper, Installment 5 of Creating a Sustainable Food Future. 2014. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

Modelling Cannabis for Excellence in Biomedicine and Equitable Wealth Distribution

by Indira Martin

Indira is a biomedical scientist based in The Bahamas

Summary: Indigenous scientific ontologies for economic empowerment

*JREVLIB EXCLUSIVE*

Interview with Francine Russell and Andrea Moultrie

Co-Founders of The Heritage Partners

Summary

In this JREVLIB Exclusive, we sit down to chat with Francine Russell and Andrea Moultrie, co-founders of The Heritage Partners, an innovative business modelled on the Pan-African concept of Sankofa, which means 'looking back to leap forward'.

.png)

JREVLIB: You guys have a very unique business model, and we love that your logo is the Sankofa bird! How does the Sankofa concept play into your overall business model?

HERITAGE PARTNERS: Yes, Sankofa!. Our Logo visually and symbolically represents the Sankofa bird. The Sankofa is expressed as a mythic bird that flies forward while looking backward with an egg (symbolizing the future) in its mouth. The Heritage Partners operate on the premise that without properly understanding the past, attempts to be forward-thinking are often futile. We critically examine the past to help understand why and how we came to be who we are today. We believe we will create effective agents for the future that will bring positive progress.

JREVLIB: Do you think that seeking of heritage can be a revolutionary act?

HERITAGE PARTNERS: Yes, the seeking of heritage is described as a revolutionary act because it's a procress that forces individuals to shape their identities and take on a responsibility to ensure we have a strong future. The Akans ( the tribe from Ghana the word Sankofa came from) believe that there must be movement and new learning as time passes. This is progress. This is the art of reclaiming our essence of who we are.

JREVLIB: Very cool. So what is the overall service that you guys provide? And can you tell us about any projects you have been involved in?

HERITAGE PARTNERS: The Heritage Partners help our clients unlock stories so they can share and preserve for future generations. We've worked with The Bahamas' small business development centre. The project highlighted notable and longstanding Bahamian businesses and celebrated the role that they have played and continue to play in Bahamian communities.

JREVLIB: What is the company's plans for the future?

HERITAGE PARTNERS: The Heritage Partners wants to make sure that what we do is accessible for everyone - which is a big part of our company’s mission. We will be launching other businesses under the same umbrella this year. We will be tapping into heritage tourism and the tech industries. We are really excited about these businesses. It will give the community an opportunity to interact with the past and bring life to it so that is not so arbitrary.

The Heritage Partners: Francine Russell (l) and Andrea Moultrie (r)

Resilience: A Series

by Florence Beauredon

Filled with a deep-seated spirit to fight untold injustices of the struggles of people of color, Flo has devoted her life and art to uplifting an entire race of people, one brush stroke at a time. (Sheila Anderson, writer & biographer)

Summary: Four artistic pieces inspired by the amazing Pan-African spirit of Resilience

AngeLiberty Davis

Ankhcestors (Awakening to the Power of the Ankh)

Black Love Roots

A Guardian Angel

About Us

JREVLIB was established in Nassau Bahamas by a cross-sectoral and international group of revolutionary scholars, it is contextualised by an urgent need to provide novel ideas and practical solutions for the economic and social liberation of peoples from the global south.

JREVLIB distinguishes itself through its core tenets of accessibility and availability to the wider public, and its intentionality of purpose for creating and sharing concepts and knowledge related to the pursuit of revolution, liberty and dignity.

In this light, our mission is to facilitate a space for the presentation of revolutionary ideas that can be widely disseminated to the public. The end goal of this mission is to stimulate the organic ingenuity of readers and viewers, as well as our contributing writers, towards the coordinated, informed and evidence-based realisation of true revolutionary change, particularly in the global South.

The material published will be urgent and topical thereby facilitating discussion, debate and decision making for societal transformation.

Submissions are welcomed in a variety of formats (article, art, music, photography, video etc) and subject matters (law, science, history, philosophy, economics, spirituality etc), from both academic and non-academic contributors.

Please contact us at journalofrevolution@gmail.com if you are interested in contributing.

Also please check out the Seshat Public E-Library, where you will find our collection of e-books, and you can even contribute to our collection. Visit Seshat here: