The Journal of Revolution and Liberation

Volume 1, Issue 3 (Oct 2018): "Into Freedom"

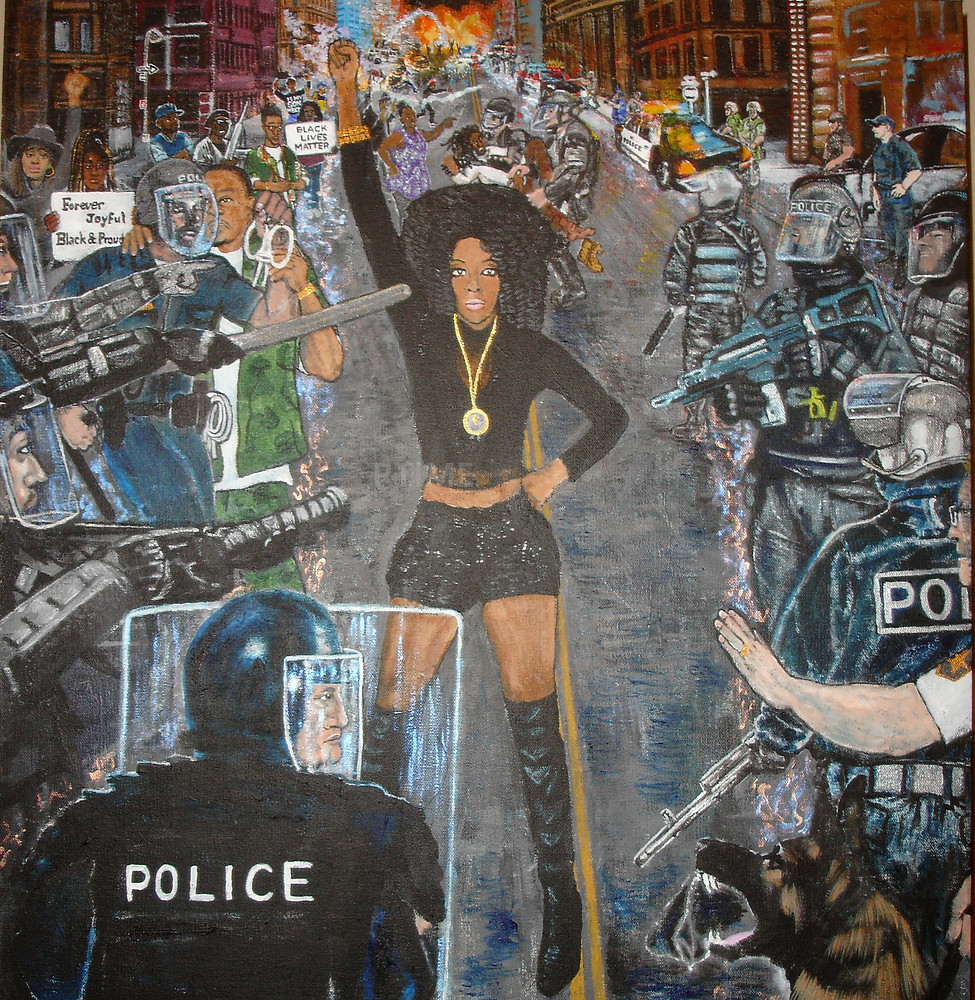

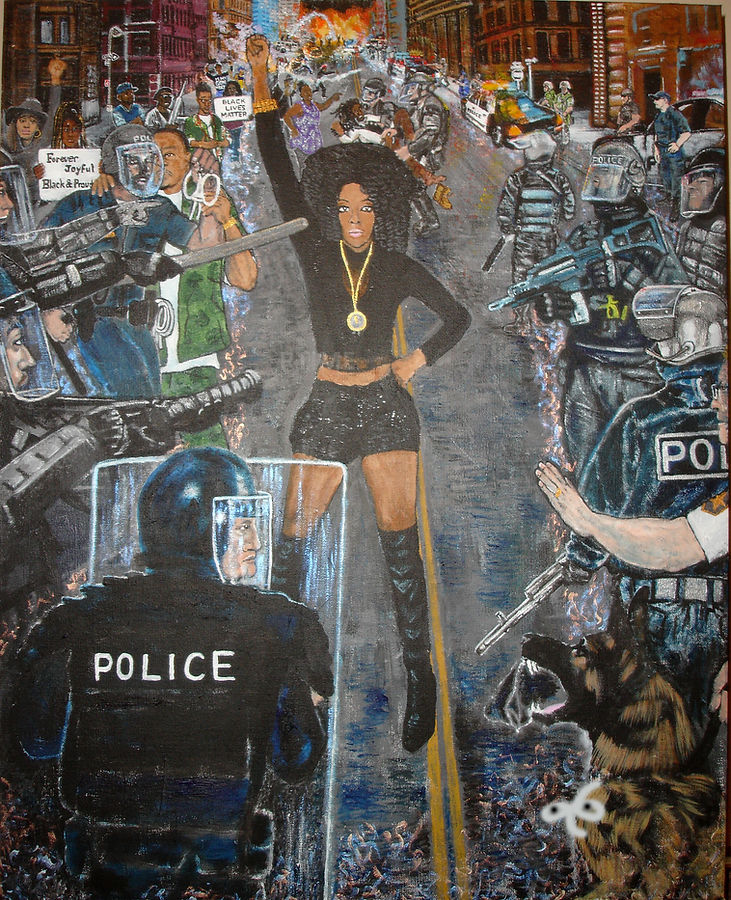

Cover Art: E-Volution by Leecasso

Journal of Revolution and Liberation

Volume 1, Issue 3(Oct 2018): "Into Freedom"

Table of Contents

1. JRevLib Issue 3 Editorial Summary

FLOW A: REFLECTION

2. "What Would Our Ancestors Say? A Reflection on Bahamian Emancipation Day", by Chris Davis

FLOW B: RE-CREATION

3. "Me the Caribbean Man", by Michael Pierre

FLOW C: RESISTANCE

5. Jariya: A Mini Art Collection, by Flo Beauredon

6. "Legalize It and I Will Analyze It", by Indira Martin

Editorial Summary: "Into Freedom"

In the Bahamas, there is an island called Eleuthera, which means ‘freedom’ in Greek. It was so named by the Eleutheran Adventurers, a group of pilgrims who in 1648 fled persecution in England to seek religious freedom on that loftily named island. But, the adventurers brought enslaved Africans to the ‘Freedom’ island: freedom for some was enslavement for others. In the last three months, Eleuthera has come to the fore of both national and international discourse, as Disney corporation has secured the purchase of what is perhaps the most pristine beach on the island, for use as a cruise ship port. Hopeful for employment opportunities, the locals (many of them descendants of those original enslaved Africans of Eleuthera), largely approved the Disney purchase, of their own 'free' will.

Also in this last quarter, in August, we celebrated the 185th anniversary of the Emancipation of enslaved Africans in Caribbean nations formerly colonised by the British. Despite this ‘emancipation’, forced apprenticeship continued for several years afterwards, and more than a century of colonisation and apartheid followed. In addition, to this day, a lack of economic independence throughout the African diaspora makes us prey for neocolonial interests (like Disney) as well as for large economies (such as the US, EU and China) and global economic structures (such as IMF/World Bank and WTO). Pressed with these Realities, we must truly ask, Are We yet Free?

During the same period, we have watched the valiant struggle of Bobi Wine (Robert Kyagulanyi) in Uganda, persecuted for his opposition to the political status quo. In his recent song ‘Freedom’ he says ‘What is the purpose of liberation when we can’t have a peaceful transition…freedom fighters become dictators, they look pon the youth and say we distractors’. This phenomenon of a New Generation coming forward to challenge the entrenched and ageing postcolonial political leadership is being seen elsewhere in the diaspora, where political independence has failed to transition successfully into economic independence, an indication of the reality that We are not yet Free.

JRevLib Issue 3- ‘Into Freedom’ includes a brilliant and bold analysis of race relations in the Bahamas, in which revolutionary legal and race scholar Dion Hanna delivers a sobering prognosis of the state of race relations in Bahamas, in the context of the global history of racism. In this, he shows that both Black and White Bahamians are afflicted with ‘historical amnesia and cognitive dissonance’ that can only be solved by indigenous analysis of race matters, socio-economic empowerment of the Black majority and a redefinition of the Black Bahamian identity.

The theme of cognitive dissonance is continued in ‘Me the Caribbean Man’ by Michael Pierre of Trinidad and Tobago; in this emotive piece we feel the struggle of claiming an identity in the context of the Caribbean where there has been a constant assault on the African cultural identity. The author ends by saying he is ‘now christened a new entity’. This concept of the power of self-creation is also confidently explored in ‘Birth’ by Arvis Mortimer in which she asserts that ‘in whatever moment I choose, I can become a new me’. Both these pieces are reminiscent of Franz Fanon, who has said, ‘In the World through which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself’.

A beautiful art series by Flo Beauredon from France via Atlanta, USA starkly counterposes the sad history of slavery in ‘Silent Scars’, as well as the continuation of brutality against people of colour in the present-day in ‘Jariya (Resistance)’, against our hopes and dreams of peace, freedom and serenity, in ‘She said PEACE’ and ‘Freedom Dancer’. We are called to close this yawning gap between our aspirations and our Reality.

So, how do we progress ‘Into Freedom’? In the video submission ‘Legalize it and I will analyze it’, Indira Martin proposes the legalization of cannabis as a means of actualizing greater economic and scientific independence in the Caribbean. Additionally, in a continuation of Beauredon’s ‘Jariya’ theme, an excellent article on Bahamian emancipation by historian Chris Davis highlights the key means by which Africans in the Bahamas and wider diaspora have historically progressed ever deeper ‘Into freedom’: through active Resistance.

Indeed, this concept of Resistance emanates from the striking Issue 3 cover art, ‘E-volution’, by Leecasso of California, USA, which depicts a lone woman in the chaos of the white supremacist prison-industrial complex, raising her fist defiantly to the sky. This image communicates the core tenet of JRevLib Issue 3: that we will go forward ‘Into Freedom’ no matter the obstacles, and we will do so because it is the Human imperative.

Therefore, in the name of the Ancestors, and motivated by the Hopes and Dreams of our Descendants yet unborn, We must PUSH ‘Into Freedom’. We Must break the chains of mental slavery. We Must Create and Re-create. We Must Reclaim. And in the face of oppression, We Must Resist.

What Would Our Ancestors Say? A Reflection on Bahamian Emancipation Day

By: Christopher Davis

Christopher is a Bahamian historian and researcher and co-founder of Afrikan Ebube, a pan-African educational forum

Summary:

What would the ancestors think about our commemoration of Emancipation Day in the modern Bahamas? This article outlines the struggles of Africans in the Bahamas, and their resistance to enslavement, as a challenge to the fallacious Eurocentric 'Wilberforce' narrative offered as historical (mis)truth. A cogent argument is put forward for a re-framing of the emancipation narrative to celebrate and remember the endurance of the Ancestors.

On August 1st, 1838 chattel slavery ended in the Bahamas and most of the British 'colonies.' Often when speaking about emancipation, the focus is on people like William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and even Queen Victoria. They are often presented as allconquering heroes who are almost solely responsible for the end of slavery in the British Empire. The official Abolitionist movements coming out of Britain as well as the pioneers of the Industrial Revolution are also sometimes portrayed as the only major driving-forces of emancipation. Many of the British Abolitionist movements were somewhat disingenuous, though more progressive than their counterparts still overtly racist. This is usually coupled with depictions of enslaved black people begging and pleading, whose only hope for freedom rested on solely the efforts of white parliamentarians, philanthropists and clergymen. The rhetoric of many British abolitionist movements usually stopped short of perpetuating any real social equality and retribution after dealing with the removal of chattel slavery. However, this could not be further from the truth. People like Olaudah Equiano, Mary Prince and Ignatius Sancho were put in the forefront and galvanized the abolitionist movements but often still treated as second class citizens within the groups. In the film Amazing Grace, Wilberforce is highlighted while Equiano is reduced to minor role with a few lines and cameos. We have martyrs, heroes, heroines and people who possessed the sense of divine fearlessness who are also the movers and shakers of British Emancipation and in a broader context even more so.

Black emancipation was truly pushed and carried through by the enslaved themselves, while white abolitionist only debated and signed documents in an ivory tower. Africans throughout the diaspora were constantly fighting against their enslavement in a variety of ways to differing results. The unknown enslaved girl in the most desolate corner of the Bahamas during slavery who feigned sickness or ran away even for a day; causing her enslaver the most meager of economic loss; has contributed vastly more to the ending of slavery than any British dignitary who has never experienced chattel slavery. Every action, no matter how large or small, contributed to the fact that not only was slavery unjust, unethical and evil but it was also dangerous for the colonizer and enslaver. These acts against slavery on every level made the institution unstable from within, and were crucial in realization that the notion of ‘perpetual’ slavery is impossible.

In paraphrasing Historian Bayyinah Bello, “resistance to slavery didn't start in Britain and/or France but on the first slave ships, where the first enslaved Africans fought for their freedom." Within the global African Diaspora, we are encouraged to make heroes of those who are not only outside of our own communities but directly benefited from the indescribable horrors our ancestors and kinsman endured. Our two most prominent statues, Christopher Columbus and Queen Victoria are obvious illustrations of this part of our neo-colonial indoctrination. Another blaring example was unveiled weeks ago; The Statue of Woodes Rogers, our first colonial governor who helped strengthen the British Slave Trade before being propagandized as the man who put an end to Bahamian piracy and “restoring commerce”.

The Bahamas has also played its own unique role leading up to British Emancipation. Below are just three broad major factors leading up to Emancipation and how the Bahamas contributed:

RESISTANCE BY THE ENSLAVED:

The role of the enslaved and other blacks was central in the push for emancipation. The Haitian Revolution, Maroons of Jamaica and Guyana, African Kingdoms of Brazil and Colombia and many other revolts and acts of 'divine fearlessness' resonated through the minds of the major beneficiaries of slavery and opponents of slavery alike. By the early 1800s, the enslaved created a real rational fear of African people one day rising up and not only freeing themselves but turning the ingrained social hierarchy upside down. The concept of the Bahamian Saltwater Underground railroad falls into this category. There are 29 documented slave ships where enslaved people were freed and settled in places like Adelaide, Gambier and the various ‘Freetowns’ and ‘Congo Towns’ on Family Islands. The people who came off of these ships were generally referred to as Liberated Africans. The way our industrious mariners have historically exploited other ships is well documented but revolutionary acts against slavery are rarely mentioned. Settlements like Red Bays, Andros were peopled by Seminoles who were escaping enslavement and genocide in Florida in the early 1800s. They were brought there by “bold captains of sloops from the British Bahamas who offered transportation across the Gulf Stream.” Even the great Olaudah Equiano was shipwrecked in the Bahamas and rescued right in time by Bahamian mariners and brought to Nassau.

In the Bahamas, virtually every island had forms of resistance to varying degrees. In Long Island 1809, Monday, Abram & Neptune Pratt murdered their notoriously cruel overseer Andrew Holmes on Thomas Pratt's plantation. They were summarily executed and Neptune’s body was put on display as a warning to other would be rebels. The enslaved of the Johnson Plantation in Eleuthera and Fergusons in Exuma boycotted for better conditions on the plantation in 1833. The demographics of Abaco are partially reflective of the Black Loyalists who held their ground on the mainland, fighting and refusing to re-enslaved. This made it more difficult for white loyalist to establish slavery on parts mainland Abaco. This is well documented in recent the recent works of Dr. Christopher Curry, Bahamian Historian; himself a direct descendant of Abaconian Loyalists. Dr. John Henrik Clarke states that "every country in the Americas had Maroon societies without exception." There were maroon societies at various times during Bahamian Slavery at Blue Hills with the death of a leader Indian John in 1786 and the infamous Jem Matthews (early 19th century) identified as the major leader throughout the following decades. They refused to be enslaved or to conform to racial societal norms and chose to live in as much autonomy as could possible in the Bahamas’ unique environment. Uniquely, Negro Town (present day Bain & Grants Town) was viewed as a place as unsafe for whites until colonial governors officially brought it into the societal fold; a pseudo Petit Maroon society right over the hill “behind the hospital” or “south-west of Government House.” Throughout the 1780s to the early 19th century this bastion of black autonomy was seemingly controlled by Black Loyalists who established churches and friendly societies in the area that stand to this day. Junkanoo is based upon an Akan General in present day Ghana who fought against the British and Dutch control of slave trading forts for years; Quamino, who planned to take over the Bahamas and possibly sail to Africa, may well have been among John Canoe's Lieutenants enslaved by the British after decades of fighting.

Dick Deveaux and his family of Golden Grove, Cat Island (1831) and the French Negros led by Bethune Lockhart (1797) risked it all in the name of basic human rights and freedom. The revolt on the ship “The Creole” was most successful slave revolt in United States history but took place entirely in the Bahamas. Just east of Abaco the slaves led by Madison Washington and Elijah Morris mutinied and took the ship and sailed it to Nassau after learning that Liberia was too far. Morris sparked the revolt by lowering the unsuspecting first mate below deck and fired the last shot of the mutiny. Bahamian mariners encircled the ship and prevented the Americans from retaking it and sailing on to Cuba. This incident resulted in the freedom of over 140 slaves with only two of them dying. Elijah Morris remained in the Bahamas with his wife Nancy Barton and they settled in Gambier where he participated in the liberating of other Africans and Creoles from slave ships. Some of his descendants reside in Gambier to this day. It is alleged that first time Morris met his wife-to-be, was when he helped liberate her from slavery, something that happened among several couples onboard the ship. Pompey and the Rolle slaves were almost in a constant state of resistance in the years leading up to emancipation. Through ingenious boycotts, the Rolles in Exuma were called the "most disagreeable" during the apprenticeship period and the former owners where happy to part with the land after receiving compensation; absolutely nothing to do with any notion of benevolent slave masters as we were sometimes led to believe. Literally thousands of Bahamians share kinship with these historic people, with ‘Rolle’ still the most prevalent surname in the Bahamas. Many of these stories resonated on both sides of the slavery argument at home and abroad.

REPORTED INCIDENTS OF CRUELTY

In the early 19th century, reports of cruelty to slaves were being more soundly documented and many came from the Bahamas. In fact, there was rarely an A Monthly Anti- Slavery Reporter without the Bahamas mentioned in it. The Bahamas was famous for excess cruelty toward female slaves, often times involving Assembly members and influential business men within the community. Mother and daughter Shelah and Florah Dames spent their early years raking salt on Long Cay and Little Exuma with their children. Henry Adderley had a reputation for cruelty and was exposed when Florah revealed in secret to the Governor J.C. Smyth that her mother had miscarried because she had been punished in the workhouse. Adderley attempted to sell them away to avoid getting a slap on the wrist and to punish their resilience. In a story with a bitter sweet end, the family ended up together back with their original ’owner’ but in little Exuma as salt-rakers. This was one incident of many that appears in the “Governor’s Despatches” through James Carmichael Smyth’s tumultuous tenure.

Pompey's Revolt was magnified upon realization by the enslaved that several of their women were severely beaten, two of them were with child. These acts of cruelty were overseen by Robert Duncombe and John Anderson who were long time assembly members and among the most influential men in the Bahamas at the time. In 1831, Alick Farquharson thoroughly beat James Farquharson with a metal bludgeon. James was the mulatto son and overseer of Charles Farquharson in San Salvador, with a reputation for having his way with the women on the plantation. Alick bludgeoned James in response to the whipping of a young family member for mounting a mule on the wrong side. The conflict between the two had strong undertones of an anomalous love triangle and magnified by Alick consistently referring to James as ‘Jim’ (slaves were required to address their superiors with master, sir, mister etc). John Wildgoose found himself under scrutiny of Governor Smyth. He had ordered two severe floggings of a slave named Phoebe. The second flogging claimed the Governor could not have been for any reason because it happened while still confined for the first; and couldn’t possibly have committed an offence to warrant the second. (There was also a rule for allowing lashes to heal enacted several years earlier). In the early 1830s, Ben Moss was given the cruelest sending off by his would be former enslaver within the last hour before his manumission. This was carried out by Henry and Helen Moss, a married couple in Crooked Island who were infamy extended far beyond Bahamian shores.

The most powerful and influential cases in the Bahamas that influenced widespread emancipation was the story of 'Poor Black Kate.' In 1826 on Henry and Helen Moss' plantation in Crooked Island, a young slave names Kate was murdered. Kate would have found herself in an unbearable situation, from a domestic slave to raking salt for hours a day with her chastity perpetually at risk. The Anti-Slavery Monthly Reporter mentioned her in almost every issue since late 1826. Entitled "Cruelties Perpetrated by Henry and Helen Moss, On a Female Slave in The Bahamas.” Defiant every step of the way, this martyr of the African Diaspora endured everything from severe floggings, over work in the field (she was originally a domestic) spending weeks in a sweat box and rubbing pepper in her eyes to prevent her from sleeping. She finally died while working in the field and the ensuing court case ended with a proverbial slap on the wrist. However, her story was always referred to concerning on cruelty of slaves and was central in pushing towards amelioration acts particularly the flogging of female slaves throughout the British slave-states. In every case without exception, the perpetrators of these cruelties received resounding support by the Bahamian white and planter class. Even the infamous Moss’ character was vigorously defended and anger was boldly expressed at the fact that they were been punished at all.

AFRICAN/BLACK LITERARY CONTRIBUTIONS

There is a long list of formerly enslaved people whose narratives galvanized all modes of movements towards emancipation. Two of the most significant ones are Olaudah Equiano and Mary Prince both of whom have connections to the Bahamas. Even from beyond the grave, Olaudah Equiano was the true driving force behind the abolitionist movement. Eqiuano purchased his freedom in 1766 after making money as a jack of all trades and was very fortunate to have a more humane enslaver. His writings were deeply influential to Wilberforce on a personal level. Equiano tirelessly toured and taught Britain and brought the harsh realities of slavery to the doorsteps of pro and anti-slavery voices alike. He was kidnapped in Africa and sold into slavery with a Portuguese name forced on him: Gustava Vassa. He was a member of a strong abolitionist group called Sons of Africa, and the narrative of his life was one of the convincing documents in Britain abolishing the slave trade in 1807. His story still resonates today and he represents a truly powerful rags to riches story comparable to Frederick Douglass and Robert Smalls. Amazingly, he was on a vessel travelling to Georgia that capsized in the Bahamas. They sought refuge on a very desolate island and just as all hope was lost they were discovered and brought to Nassau. If Bahamian Mariners didn’t save his life, the world may only have been graced with a small portion of his talents. He is a pioneering figure in literature, politics and especially abolition on a global scale. Indeed, if a sole award for influencing British emancipation in 1838 was to be given one person, it would undoubtedly have to be Olaudah Equiano. Born in African, he experienced kidnapping, the march to the coast, slave dungeons, the middle passage and slavery in varied scenarios. He also resisted slavery as a slave, an author and probably more so from the grave while the contemporary history books have consistently given William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson almost the majority of the credit.

Mary Prince's autobiography gives sound examples of the harsh realities on the Bahamian Salt plantation and unequivocally dispels the myth of slavery being milder/easier in the Bahamas. Enslaved in the U.S.A., Antiqua, England and the Bahamas, here most difficult and traumatic experience was on a typical Salt plantation in the Bahamas, a seasonal commodity produced on every Bahamian Island. Crooked Island, Acklins, Inagua, Little Exuma, Ragged Island, Long Cay and the entirety of the Turks and Caicos were all islands whose economies were dependent on the raking of salt. The cruelty that Mary Prince received witnessed was so bad that it is alleged that it soften the hearts of the most avid pro-slavery voices. She greatly influenced global abolitionist movements, pointing at her experience on Grand Turks being the worst period of her life as a slave. She wrote "History of Mary Prince" which arguably became one of the most influential factors during the push for British Emancipation and was the first written by a black woman in Britain. Prince became one of the most influential people in the world at the time. In unapologetic fashion, she lamented "I have been a slave myself—I know what slaves feel—I can tell by myself what other slaves feel, and by what they have told me. The man that says slaves be quite happy in slavery—that they don't want to be free—that man is either ignorant or a lying person. I never heard a slave say so. I never heard a Buckra (white) man say so, till I heard tell of it in England." After a very public and victorious legal battle with an influential nemesis, little is known about the remaining years of her life. It is believed she may have left the spotlight for her own safety. Another theory is she may have been kidnapped and/or murdered and never heard from again as theorized in with African American Narrative writer Solomon Northup.

CONCLUSION

Today, for most Bahamians of all walks of life Emancipation Day has become like any typical holiday where we are only happy for the long weekend. Of all countries with a similar demographic and history (In the context of British colonialism) the Bahamas has among the least ceremonious emancipation celebrations. There seems to be a great divide crated between our enslaved ancestors, our shared glorious, complex and painful history and Black Bahamians who are alive today. The Ethiopian African Black International Congress has always held the prestigious holiday in the highest honor, with lively annual marches; all too often very poorly attended. Gambier Day is another official celebration, also perpetually poorly attended. Surely if the black Diaspora knew of its historical significant Americans may also develop a profound appreciation and travel to celebrate emancipation with us. Even Black Point Exuma and Cat Island, two vanguards of Black Bahamian Revolutionary action and strongholds, host their Regatta’s when the holiday is celebrated with theme of Emancipation on the backburner. Of course, we are not do not share the brunt of the blame but in recent times have perpetuated the great disconnect between ourselves and our ancestors. We are constantly bombarded with procolonial propaganda and African/Black Bahamian History has been a dormant volcano for far too long. Many Bahamians justifiably possess the name ‘Wilberforce’ in commemoration of emancipation but you cannot find a single one named after Olaudah. As a nation, we have consistently failed to truly commemorate those that fought, died and endured so that we can live and breathe today.

We can proudly say that our ancestors literally and figuratively built the ‘New World’ for others to enjoy and lay the foundations of the strongest economies in the world today. Emancipation Day is a day for celebration, so there is nothing wrong with having fun on the holiday. However, let us not lose sight of the true meaning of this precious day; so meaningful to the entire African Diaspora whether we choose to acknowledge it or not. Emancipation Day should celebrate not only our ‘Blackness’ but our strength and historically superior humanity. We must do better in commemorating and showing love for our ancestors as they would us as their great-great-great grandchildren. On Emancipation Day, we must show appreciation for our ancestors who endured, without whom none of us would be alive today.

Me The Caribbean Man

By Michael Pierre

Michael shared a womb for 7 months and was born in 1988 in Trinidad and Tobago. His interests are art, music and writing mostly for himself. He has been described as a free spirit and water-loving.

Summary

'Me The Caribbean Man' highlights some of my experiences and the stories told to me by others in a condensed format; touching ethnic and racial divides and history. It is my hope that debate and frustration comes from this piece. Debate and frustration can lead to constructive solutions which forges change. How can we overcome? Note a solution is not given because just like the interpretation it is up to the reader to investigate, discover and share solutions; The Start To The Great Conversation and The Beginning of Healing.

How does one define the classical Caribbean Man?

The Caribbean man is a demonstrative product of forgery that is, somewhat close to the real thing; counterfeit but useful. This is the definition passed from lips to ears and encoded in genes, illustrated as phenotype. We nurtured fields with our lives, now our roots grow strong. We were displaced from our homes; being told the land belongs to a queen unseen in a language unknown. We were the messengers who laboured through battles with the sea seeking sovereignty, expanding our scape and the monarch’s empire. The Caribbean man is complex. Complexity not built from interconnected simple pathways but complexity entangled in complexity. How do we decode the Caribbean man?

What are the results of the Caribbean Man; language, music and self-expression?

When compared to West Africans we are similar but yet counterfeit. Indians; we are not Indian enough. And in the white man lands, we are black despite the lack of our melanin. The Caribbean man is new and emerging. Creators through discretion; hiding to worship Gods of the old, disguised in the realm of Catholicism, even drums penetrate through the sombre rituals of the church. We learning of a God that loves us and pray to Gods to protect us. Being bred to create perfect specimens which were robbed of knowing their fathers. Birthed in chaos but “civility” is expected. We were killed by touch even by breath, bodies confused by foreign entities and babies told you were raged-filled cannibals. Breeding self-fear and self-hatred, the mental and genetic trap placed and its potency unquestionable. Now blessings turn to curses, my ancestors reaped rewards and never considered the consequences of their actions, now I must hide from those who were enslaved, trapped but now free and those freeing others - I quake because now I must suffer.

Is the Caribbean Man diseased?

The future holds retaliation and war. Lands reclaimed, shackles free and unknown enslavers exposed and forced to see the light and understanding terribly instilled. And all those who checked Others in the box for so many years along with the first, the free, the counterfeit, the newly enlightened, the fighters of war and the silent well-wishers even those who don’t give a f**k can just say I am definitively Caribbean.

We are pidgined,

Limitless and the face futurism.

Formless and abundant in diversity

Where ancestors congregate and the counterfeit is now christened a new entity.

Birth

By Arvis Mortimer

Arvis is a public health professional from The Bahamas

Summary:

Birth is a poem that expresses one of the author’s fundamental beliefs, that individuals (particularly able-minded persons) are inherently agents of their lives and can be the directors of their destiny. It is hoped that the key themes of personal power, potential and possibility are easily identified and it is recognized that even though one’s body may be relegated to a specific location, or a particular state, transcendence beyond limiting self-perceptions, self-definitions, or even the internalization of external judgements is possible. It is the goal of the writer that each reader knows that, though not always easy, new and empowering attitudes can be adopted – contributing to revolution and liberation within; which can lead to the same without.

Let me tell you a secret

I have been born more than once

Through the portal between

The world and my mother’s womb

I entered fairly unannounced

Newly released with a novel start

This was my first birth

But it was not my last

For

Like you

I was endowed

With power and creativity

So in whatever moment I choose

I can become a new me

I have permission to change course

I do not have to remain the same

I can blossom into something different

I can even rewrite my name

I have the liberty to escape

Any self-imposed pain

I can embrace my singularity

And choose those with whom I would want to hang

Birthdays do happen

Many times in one day

Because when I need a restart

I can be as when I first came

Fresh, free and purely me.

Jariya: A Mini Collection

By: Flo Beauredon

Originally from France, and currently residing in Atlanta, Georgia, Flo has a passion for Freedom of expression and honesty, as well as being kind to one another, and always defends the causes of the disadvantaged ones. Combining themes of awareness, symbolism of hidden truths and using her paintbrushes as a whistle blower at times, her paintings are raw and symbolic.

Summary:

JARIYA is a piece representing the oppression of the Black Man through centuries (1700’s – 2000’s) Jariya means “Resistance” in Hausa language (most spoken language in West Africa). This painful history is also reflected in the second piece, 'Silent Scars', and following this, out of a historical collage of struggle and resistance we see a lone woman emerging with a message of peace in 'SHE SAID PEACE'. The series ends with 'Freedom dancer', which evokes a sense of serenity, an objective to be claimed in the chaotic horror of white supremacy.

Jariya

Silent Scars

She Said PEACE

Freedom Dancer

Legalize It and I Will Analyze it

By: Indira Martin

Indira is a biomedical scientist based in Nassau, Bahamas

Summary:

Marijuana (scientific name cannabis) has been used medicinally for thousands of years, throughout the world. In recent years, following decades of prohibition, there has been renewed interest in medicinal cannabis, and a surge of research and increased liberalization of the cannabis plant in North America and Europe. Despite prohibition, The Caribbean has historically played a pioneering role in medicinal cannabis research and use. Therefore this video argues for the full liberalization of cannabis in the Caribbean, to enable Caribbean scientists to contribute to the rapidly emerging global research into biomedical cannabis use, thereby catalyzing a Biomedical Revolution in the Caribbean.

Cognitive Dissonance and Historical Amnesia: Racism and Race in a Bahamian Context

By: Dion Hanna

Dion Bahamian legal scholar, lecturer, researcher and community activist based in the UK.

“I plucked my soul out of its secret place, And held it to the mirror of my eye, To see it like a star against the sky, A twitching body quivering in space, A spark of passion shining on my face. And I explored it to determine why

This awful key to my infinity Conspires to rob me of sweet joy and grace. And if the sign may not be fully read, If I can comprehend but not control, I need not gloom my days with futile dread, Because I see a part and not the whole. Contemplating the strange, I’m comforted By this narcotic thought: I know my soul.” Claude McKay 1

It has been asserted that the concept of race has always been a vital component in the shaping of Bahamian history and national identity.2 In this regard, as we are advised by Nettleford in respect of Jamaica, but equally relevant to the Bahamas, race is more than “yeast for dough” in the social fabric of Bahamian society3. Further, Adrian Gibson has indicated that locally, although the “unambiguous and overt forms of racism” may have receded since Majority Rule and constitutional changes, in the political realm, clearly race continues to be a relevant feature of political rhetoric. He further indicates that the concept of race has “greatly shaped our society and national identity” and that its structure provides us with a “framework to address issues that may linger and persist in dividing our nation”4. Nevertheless, as we are reminded by Curry, unfortunately, in The Bahamas very little has been written directly concerning racism since independence5.

1 Claude McKay and William J. Maxwell (2008): Complete Poems of Claude McKay. Urbana, Ill, University of Illinois Press

2 Christopher Curry (2018): “Race Relations in the Post-Independence Bahamas” In The Journal of

Revolution and Liberation, Vol. 1 (2) July

3 Rex Nettleford, (2007): “Prologue: The Caribbean and Cultural Studies: More than Grimace and Colour” In Brian Meeks (ed.) Culture, Politics, Race and Diaspora: The Thought of Stuart Hall. Kingston and London. Ian Randle and Lawrence and Wishart.

4 Adrian Gibson (2010): “Is the Bahamas Mature Enough to Vote for a White Political Leader” In The Tribune, November

5 Christopher Curry (2018) supra.

However, it is important that we place our discourse in the context of the ambivalence of Bahamian national identity6. As we are reminded by Stuart Hall, we must bear in mind postmodernism's deep and ambivalent fascination with difference, including sexual difference, cultural difference, racial difference and above all, ethnic difference.7 Further, it has been indicated that the “project of identity”, whether individual or collective, is rooted in desires and aspirations that cannot be fulfilled, identity movements are “open ended, productive and fraughtwith ambivalence”.8 In this frame of reference, it is important to consider Christopher Curry's indication that even though Bahamians use the term race in vernacular discourse, the term is problematic,9 and has been described as being a “prickly subject”.10 In this regard, it is critical to bear in mind that the concept of race is an artificial construct created in the late 18th and 19th centuries, but part of a gradual process that began in the advent of the so called voyage of discovery of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Its invention was inspired by the need to justify European colonial domination and enslavement of Black people in the Americas, Africa and Asia.11 Columbus began the process by the demonization of the Caribs, creating a false image of them as cannibals and by his stereotyping of the Taino people as a people in need of the civilizing influence of western Christianity and fit for enslavement to exploit gold, pearls and other natural resources12.

5 Christopher Curry (2018) supra.

6 Arthur Dion Hanna jr. (2011): Decoding Fault Lines of Life and the Enigma of Being: Immigration

Policies and the Formation of National Identity in the Caribbean. Paper Presented to the International Bar Association's Rule of Law Seminar - The Rule of Law: Immigration Policies in

the Caribbean. Hilton Hotel, No.1 Bay Street, Nassau, The Bahamas, 25th February; (2014): Distant

Echoes Of Pan African Identity: The Discordant Resonance Of Cultural Resistance And Ambivalence Of Identity In A Diasporan Context. Paper Presented to the 43rd Annual Conference of the British Society for Eighteenth Century Studies, St Hughes College, Oxford University: 8-10 January

7 Stuart Hall (1992: 23): “What is This 'Black' in Black Popular Culture?” In Gina Dent (ed.) The Center for the Arts, Dimensions in Contemporary Culture, No. 8: Black Popular Culture. Seattle. Bay Press

8 James Clifford (2000:95): “Taking Identity Politics Seriously: The Contradictory Stony Ground” In Paul Gilroy,+Lawrence Grossberg and Angela McRobbie (eds.) London. Verso Press

9 Ibid.

10 Adrian Gibson (2010) supra.

11 Eric Eustace Williams (1964): British Historians and the West Indies. Brooklyn N.Y. A& B Books; George Boulukos (2008): The Grateful Slave: The Emergence of Race in Eighteenth Century British and American Culture. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press; David Olusoga (2015): “The Roots of European Racism Lie in the Slave Trade, Colonialism and Edward long” In The Guardian 8 September

12 Basil Davidson (1992): “Columbus: The Blood and Bones of Racism” In Race and Class Vol.33 No.3, 17-25; Jan Carew (1994): Rape of Paradise: Columbus and the Birth of Racism in the Americas. Brooklyn. N.Y., A&B Books; R. Carew(2006): The Rape of Paradise: Columbus and the Origins of Racism in Americas. Astoria, N.Y, Seaburn Publishing Group

European xenophobia and racial othering was manifest in the expulsion of Moors and Jews in Spain in 1609 and the expulsion of “Blackamores” by Queen Elizabeth I in England in 1598.13 Early on, the Spanish began a process of racial classification, othering and demonising non-White peoples. This was catalyzed by the fact that, in the aftermath of their conquest of the Americas, the early colonists, who were soldiers from Iberia, began, from the 15th century, to have sexual relations with Native Americans, and subsequently, with Black African slaves. By the 17th century, the widespread race mixing became a concern for the Spanish monarch and racial purists in Spain. This led to a pyramid of race differentiation that became known as 'castas', with the White race being at the apex and Black Africans at the base of this racial paradigm. In a series of paintings known as 'Las

Castas', to explain this complex division of humanity, Spanish artists were commissioned to graphically portray the essence of this racial pyramid14. This racial paradigm, was a means of political and social control and determined status in society. At the top of the racial pyramid were those of pure Spanish blood born in Spain; just beneath them were those of pure blooded descent born in the Americas, known as Crillos. Under this umbrella of White supremacy were the Native American People and in descending order Mestizos, who were a mixture of Spanish and Native American; Castizos who were a mixture of Mestizos and Spaniards; Cholos a mixture of Native American and Mestizos; Pardos, a mixture of Spanish, Native American and Black African; Mulattos, a mixture of Spanish and Black African; Zambos, a mixture of Native American and Black African, with Negros, pure blooded African people at the base of the racial and social pyramid15.

13 Peter Fryer (1984): Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain Since 1504. Atlantic Highlands N.J., Humanities Press; Emily C. Bartels (2006): “Too Many Blackamoors: Deportations, Discrimination and Elizabeth I” In Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, March

14 David Cahill (1994): “Colour by Numbers: Racial and Ethnic Categories in the Viceroyalty of Peru” In Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 26. Available online: <https://web.archive.org/web/20131029200024/http://people.cohums.ohiostate.edu/ahern1/SpanishH680/secure/Cahill%20-%20colour%20by%20numbers%2C%2012%20pages.pdf> ; MariaElena Martinez (2000): “Space Order and Group Identities in a Spanish Colonial Town: Puebla de los Angeles” In Luis Roniger and Tamara Herzog (eds.) The Collective and the Public in Latin America: Cultural Identities and Political Order. Brighton, UK/Portland Oregon, Sussex Academic Press; (2004): “The Black Blood of New Spain: Limpieza de Sangre, racial Violence and Gendered Power in Early Colonial Mexico” In William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd edn. Vol. LXI July; Sarah Cline (2015): “Guadalupe and Casatas: The Power of a Singular Colonial Mexican Painting” In Mexican Studies, Vol. 31 (2); Rebecca Earle (2016): “The Pleasures of Taxonomy: Casta Painting Classification and Colonialism” In the William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 73 (2) July

15 Ibid.

Elsewhere in 18th century Europe, European biologists and physicians, such as Carl Linnaeus16, Charles White17, Benjamin Rush 18 and Cristoph Meiners19, began to classify humanity into separate races in a pyramid which placed White people at the top, as the superior race and Black people at the base, as being inherently inferior. However, it is in the wake of Darwin’s social theories

expounded in his book The Origin of the Species20, in the 19th century that biological theories were developed to provide a scientific basis for racial difference. Scientific racism was developed by philosophers and scientists such as the French aristocrat Arthur de Gobineau21, who advanced the concept of three races, White, Black and Yellow and argued that race mixing would lead to the collapse of culture and civilization. His racist theories asserted that the White race originally possessed a monopoly of beauty, intelligence and strength and were inherently superior. His theories were highly influential with slaveholders in the Americas and more recently with the Nazi Party in Germany22.

16 Heinz Goerke (1973): Linnaeus. New York, Scribner; Norman J. Sauer (1993): Applied Anthropology and the Concept of Race: A Legacy of Linnaeus” In Annals of Anthropological Practice, Vol. 13 (1) January; Theodor Magnus Fries and Benjamin Davidson Jackson (2011): Linnaeus. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

17 Charles White and Samuel Thomas Soemmering (1799): An Account of the Regular Gradation of Man and in Different Animals and Vegetables. London, Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester; John P. Jackson and Nadien M. Weidman (2010): Race, Racism and Science: Social Impact and Interaction. New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press

18 Benjamin Rush (1786): An Oration: Delivered Before the American Philosophical Society, Held in Philadelphia of the 27 February 1786[ Containing and Inquiry Into the Influence of Physical Causes Upon the Moral Faculty by Benjamin Rush, Md and Professor in Chemistry, University of Pennsylvania; Benjamin Rush and Dagobert D. Runes (2013): The selected Writings of Benjamin Rush. New York, Philosophical Library

19 Michael C. Carhart (2007): The Science of Culture in Enlightenment Germany. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press; Nicholas Bancel , Thomas David and (Dominic Richard David Thomas (2014): New York, Routledge; Christopher Meiners (2018): History of the Female Sex, Vol. 1 and 2. (Classic Reprint) Forgotten Books

20 Charles Darwin (2009): The Origin of the Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. New York, Modern Library

21 Arthur de Gobineau (1971): Selected Political Writings. Michael D. Biddiss ed., London, Cape; (2009): The Inequality of Races. La Vergene, General Books

22 Paul Fortier (1988): “Gobineau and German Racism” In Comparative Literature, Vol. 19; Michael D. Biddiss (1971): Father of Racist Ideology: The Social and Political Thought of Count Gobineau. Littlehampton Book Services Ltd.

Others, such as the Dutch scholar, Pieter Camper23, the American physician Samuel George Morton24 posed pseudo-scientific theories of craniometry involving measurement of interior skull volume to justify racial differences. Subsequently, Social Darwinists, such as Herbert Spencer developed theories around the concept of eugenics, which emphasized the survival of the fittest, that was premised on the advancement of the superior White race through domination of the weaker races. This theory was used to justify domination of the upper class over the lower class, colonizer over colonized and the enslavement of Black African peoples25. These so called scientific theories developed on a foundation based on the myth of racial purity and ignored the historical reality of race mixing since the dawn of time26. Despite a modern day persistence of scientific theories of White racial superiority27, these crude and erroneous representations of the concept of race and racial difference have long been discredited28. However, it would be a mistake to assume that the social construct of race is some “mental quirk or psychological flaw”29. They are not “fragments of a demented imagination” but are central to the economics, politics and culture.30 Further, it has been pointed out that race has been integral to how languages have been defined over time and that language has been central to how race has been theorized and expressed in scholarship, “particularly in the western modern era”31.

23 Robert Paul Willem Visser and R. P. W. Visser (1985): The Zoological Work of Pieter Camper1722-1789. Amsterdam, Rodopi; David Bindman (2002): Ape to Apollo: Aesthetics and the Idea of Race.. ithica, NY, Cornell University Press

24 Samuel George Morton (1949): Catalogue of Skulls of Man and the Inferior Animals in the Collection of Samuel George Morton. Philadelphia, Merrihew and Thompson; (2012): Crania Americana: Or a Comparative View of Various Aboriginal Nations of North and South America, to Which is Prefixed an Essay on the Varieties of the Human Species. (Reprint). London, Forgotten Books

25 David Duncan (1908): The Life and Letters of David Spencer. New York, D. Appleton & Co.; Herbert Spenser and David Duncan (1996): Collected Writings, Vol. 2: The Life and Letters of Herbert Spencer. London, Routledge/Theommes Press

26 Thomas C. Holt (2004): “”Understanding he Problematic of Race Through Problem of Race Mixture” Paper Presented at the Interdisciplinary Conference “Race and Human Variation: Setting an Agenda for Future Research and Education, September 12-14, 2004 in Alexandria, Virginia. Available Online http://www.understandingrace.org/resources/pdf/myth_reality/holt.pdf; J. A. Rogers (2011): Sex and Race: Negro and Caucasian Mixing in All Ages in All Lands, Vol.1 The Old World. St Petersburg, Florida; Helga Rogers 27 William Shockley and Roger Pearson (1992): Shockley on Eugenics and Race: The Application of Science in the

Solution of Human problems. Scott-Townsend

28 Robert Wald Sussman (2014): The Myth of race: The Troubling Persistence of an Unscientific idea. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press

29 Franz Fanon (1952): Black Skins, White Masks. New York. Grove Press; (1961): The Wretched of the Earth. New York. Grove Press

30 Robert Blauner (2001): Still the Big News: Racial Oppression in America. Philadelphia, temple University Press

31 Anne H, Charity Hudley, Christine Mallinson and Mary Bucholz et. al. (2018): “Linguistics and race: An Interdisciplinary Approach Towards an LSA Statement on Race” In Proc Ling Soc Amer 3. 8:1-14

It has been indicated that conflicting models of classification have been used and that linguists have not developed a “cohesive theory or model of race”32. Hudley, Mallinson and Bucholz et. al. assert that linguists and others still struggle with “models of racial classification” which tend to capture the “tension of racialization” between, on the one hand “racial classification and attribution that are prescribed to a person and group” and on the other, “racial classifications that individuals or groups ascribe to themselves” with significant challenges being posed by researchers trying to examine and define “linguistic systems of cultures that they themselves do not participate in”33. This underscores the fact that it is the White western academic world that has created and engaged the language of race34 and that the issue of identity is rooted in the academic discourse of the late 18th and 19th centuries by scholars such as Descartes35, Locke36, Kant37, Hegel38, and Durkheim39. The evolution of language to describe racial identity has been a constant process and has always been a consequence of the definition of the other by the White western world. In the 16th century, the term Negro was adapted in English linguistics to describe people of Black African origins and its use continued into the 1960s40. The Term Coloured has its roots in South Africa to describe persons of mixed racial descent41 but in the United States and subsequently in the United kingdom, the term Colored was developed to describe non-White peoples during the Jim Crow era42.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Robert V. Guthrie (2004): Even the Rat Was White: A Historical View of Psychology. Boston, Allyn Bacon; John R. Rickford (2014): Increasing the Representation of Under-Represented Ethnic Minorities in Linguistics. Paper Presented as part of the Symposium : Diversity in Linguistics at the Linguistic Society of America Annual Meeting, Minneapolis Minnesota, January 2014; Linguistic Society of America (2015): Annual Report: The State of Linguistics in Higher Education. Available Online <https://www.linguisticsociety.org/resource/state-linguistics-higher-education-annual- report>

35 Rene Descartes (1983): Principles of Philosophy. V. R. Miller and R. P. Dordrecht (trans.) (eds.). Reidel; (1998): The World and Other Writings. Stephen Gaukroger (trans.) (ed.) Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

36 John Locke and Edmond Law (1777): The Works of John Locke. London, W Strachan

37 Immanuel Kant (1969): Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals. Lewis White Beck (trans.) Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill; Manfred Keuhn (2001): Kant: A Biography. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

38 Herbert Marcuse (2000): Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Revolution. London, Routledge Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (2002): Philosophy of Nature Vol. 3. London. Routledge; Georg Wilhelm Freidrich Hegel (2018): The Phenomenology of Spirit. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

39 Emile Durkheim, Kenneth Thompson and Margaret A. Thompson (2006): readings From Emile Durkheim. London, Routledge; Emile Durkheim (2013): Emile Durkheim on Institutional Analysis. Chicago, University of Chicago Press

40 Tom W. Smith (1992): “Changing Racial Labels: From Coloured to Negro to Black to African American” In Public Opinion Quarterly 56(4) 496-514

41 S. A. Tishkoff, F. A. Reed and and F.R. Friedlaender et. al. (2009): “The Genetic Structure and History of Africans and African Americans” In Science Vol. 324, 1036-44; E. Delport de Wit, W. Ragamika and C.A. Mientjes et. al. (2010): “Genome-Wide Analysis of the Structure of the South African Coloured Population i Western Cape” In Human Genetics 128(2) 245-53; Juliette Bridgette Milner-Thornton (2012): The Long Shadow of the British Empire: The Ongoing Legacies of Race and Class in Zambia. Palgrave and Macmillan 42 Nicholas Deakin, Brian Cohen and Julia McNeal (1970): Colour, Citizenship and British Society: based on the Institute of Race Relations Reports. Panther Books; Henry Louis Gates jr. (1995): Colored: A Memoir. Vintage; (2012):“Growing Up Colored” In American Heritage Magazine Vol. 62(2) Summer

The term Black was used to describe dark skinned people and was utilized by Samuel Morton in his categorization of races into a divinely based hierarchy with White European people at the top and Black Ethiopians at the bottom43. At onetime, the term was considered insulting but in the late 1960s it was embraced by the African community in America and globally and used widely in the anticolonial liberation struggle and resonated in the call for Black power44 and expressed in James Brown's song '”Say it Loud I am Black and I am Proud”45. In the 1980s and 1990s in Britain the term was adopted the African Caribbean and the Asian communities as a political sense in the struggle for empowerment and antiracism46. People of color was used primarily in the United States, and more recently in Britain, to denote all non White people to emphasize the common experiences of systemic racial discrimination47. The term Asian in Britain has been utilized to describe people from South East Asia, primarily India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.The term Ethnic Minority was developed in England and the United States by sociologists to describe people of a particular ethnic group, race or nationality, living in a country where the majority population is of a different ethnic group, race or nationality48.

43 Samuel George Morton (1849): Catalogue of Skulls of man and the Inferior Animals in the Collection of Samuel George Morton. Philadelphia, Marrihew and Thompson; Iyiola Solanke (2018): “The Stigma of Being Black in Britain”.In Identities Vol. 25 (1)

44 George Breitman (1967):”In Defence of Black Power” In International Socialist Review, January-February; Stokeley Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton (1967): Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America. New York, Vintage Books; Scot Brown (2003): Fighting for Us: Maulana Karenga, the US Organization and Black Cultural Nationalism. New York New York University Press; Jeffrey O. G. Ogbar (2004): Black Power, Radical Politics and African American Identity. Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press

45 James Brown Say it Loud I'm Black and I'm Proud {Album 1969) King Records

46 Tariq Modood (1994): “Political Blackness and British Asians” In Sociology, Vol 28 (4) November

47 Yo Jackson (2006): Encyclopedia of Multicultural Psychology. Seven Oaks CA, Sage; Alvin N. Alvarez and Helen A. Neville (2016): The Cost of Racism to People of Color: Contextualizing Experiences of Discrimination. Washington DC, American Psychological Association

48 L. Worth (1945): “The Problem of Minority Groups” In Ralph Linton (ed.) The Science of Man in World Crisis. New York, Columbia University Press; Gad Barzilai (2010): Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press; Timothy Laurie and Rimi Khan (2017): “The Concept of Minority for the Study of Culture” In Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies Vol. 31 (1)

More recently, the term BME (Black Minority Ethnic) has been utilized by sociologists to refer to non White communities initially in the United States where it was used to extend the discussion of rights beyond the term African Americans49 and subsequently adapted in Britain50. It has been argued that this label should be dismissed as being “illogical, othering and counterproductive”51 and in a UK context it has been indicated that it is not “dissimilar to categorizations used to justify

“horrendous acts of segregation in the past (and current)”52. The invention of derogatory terms to describe Black People and Asians such as Nigger, Wog, Paki, and Nig Nog are still used by racists although not a widely as in the 19th and 20th centuries. Similar abusive language has been used to describe the offspring of mating between the races such as Mulatto (same as an infertile Mule which is a product of the mating of a horse and donkey) Mestizo (Dog) half caste (someone less than whole). Despite the fact that the biological classification of races developed in the 18th and 19th centuries have long been discredited, the language of race underscores the fact that the racist paradigm continues and that the social phenomena of race and racism remains as a central feature of western societies. The fact that the western academic community continues to define racial groupings and categories, underscores the survival of the essence of White privilege. This confirms Dr Francis Cress Welsing's contention that racism is a “universal operating system” of white supremacy and domination in which the “majority of the world’s white people participate”.53 This poses a conundrum and paradox in the context of forging racial identity, in that Black people are “enslaved by a complex of inferiority”, while White people are “enslaved by superiority”, with both behaving and acting in accordance with a “neurotic orientation”.54

49 Editor (2018): “Comment: The Poverty of Labels – Why We Should Dismiss the 'BME' Label as Illogica, Othering and Counter Productive”” In the Beaver, January 25

50 A. Memon, K. Taylor and L. M. Mohebati et. al. (2016): “Perceived Barriers to Accessing Mental Health Services Among Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) Communities: A Qualitative Study in South-East England” In BMI Open. Available Online <https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/6/11/e012337.full.pdf>; Mark Brown (2018): “BME People Severely Under represented in Top English Arts Bodies” In The Guardian Monday 15 January

51 Editor (2018) infra.

52 Ibid.

53 Frances Cress Welsing (2004): The Isis (Yssis) Papers: The Keys to the Colors. Washington D.C., C W Publishing

54 Frantz Fanon (1952) supra.

As pointed out by Stuart Hall, identities are points of “temporary attachments” to the “subject positions which discursive practices construct for us”55. In this respect, identities are markers of traditional categories utilized in western social sciences, including race, ethnicity, gender, nationality and social class. Race invariably interacts with other social phenomena, including gender56, class57, ethnicity58 and age59, ever evolving in form and is amoeba like, shape shifting

and often creating new and hybrid forms invisible to Western academia and officialdom60. In this regard, concepts of race and racism have evolved throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century.

55 Stuart Hall (1996): “Introduction: Who Needs Identity” In Stuart Hall and P. DuGay (eds.) Questions of Cultural Identity. London, Sage

56 Philomena Essed (1991): Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Discipline. Sage; Sally Haslanger (2000): “Gender and race: (What) Are They and (What) Do We Want Them to Be?” In Nous 34(1) 31-55; Sapana Pradham-Malla (2005): “Racism and Gebder” In Dimensions of Racism: Proceedings of a Workshop to Commemorate the End of the United Nations’ Third Decade to Combat Racism and Racial Discrimination. Paris, 19-20 February 2003, New York and Geneva, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCR) and United Nations Educational, Social and Cultural organization (UNESCO); Shaminda Takhar (2016): Gender and Race Matter: Global Perspectives on Being a Woman (Advances in Gender Research, Vol. 21, Emerald Group ltd

57 Raymond S. Franklin (1991): Shadows of Race and Class. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press; Earl Ofari Hutchinson (1995): Blacks and Reds: Race and Class in Conflict, 1919-1990. East Lansing, Michigan State University Press; Paul Gilroy (1991): There Ain’t no Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural politics of Race and Class. Chicago, University of Chicago Press; Paul C. Mocombe (2014): Race and Class Distinctions Within Black Communities: A Racial Caste in Class. New York Routledge; Gail Dines and Jean M. Humez (2018): Gender, Race and Class in the Media. Los Angeles, Sage; Akala (2018): Natives, Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire. London,

Two Roads

58 Grant Jarvis (1991): Sport, Racism and Ethnicity. Routledge Falmer; Colin Kidd (1999): Charles Kaye and terry Linguish (2000): Race, Culture and Ethnicity in Secure Psychiatric Practice: Working With Difference. London/Philadelphia, Jessica Kingsley Pub.; Peter Osborne and Stella Sanford (2002): Philosophies of Race and Ethnicity. London, Continuum; Yasmin Hussain (2005): Writing Diaspora: Souh Asian Women, Culture and Ethnicity. Aldershot Hants/Burlington Vt, Ashgate Aldershot Hants/Burlington Vt, Ashgate

59 R. Travis Osborne, Clyde E. Noble and Nathaniel Weyl et. al. (1978): Human Variation: The bio psychology of Age, Race and Sex. New York, Academic Press; Graham Richards (1997): Race, Racism and Psychology: Towards a Reflexive History. London/New York, Routledge; James Y. Nazroo (2003): “The Structuring of Ethnic Inequalities in health: Economic Position, Racial Discrimination and racism” In American journal of Public Health, 93 (2) February, 277-284; Pat Thane (2010): “Unequal Britain: Equalities in Britain Since 1945” In History & PolicyMarch. Available Online http://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/unequal-britain-equalities-in-britain-since-1945; Equality and Human Rights Commission (2013): Putting Equality and Human Rights at the Centre of the Care Support Reform. London, EHRC

60 Gargi Bhattacharyya (2009): Ethnicities and Values in a Changing World. Farnham UK/Burlington Vt, Ashgate; James C. Peterson (2010): Changing Human Nature: Ecology, Ethics, Genes and God. Grand Rapids, Mich, Eerdmans Pub Co.; Arthur Hanna (2011): Land and Freedom – A Return to the Fishing Village: Sabbatical Essays of a Legal Aid Lawyer. USA, Createspace/Karadira Blackstar; Nazila Ghanea (2012): The Concept of Racist hate Speech and its Evolution Over Time. Paper presented to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination’s Day of Thematic Discussion on Racist Hate Speech, 81st Session, 28 August 2012, Geneva.

Available Online https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CERD/Discussions/Racisthatespeech/NazilaGhanea.pdf; Lindy

Orthia, Emma Rhys and Holly Rose et. al. (2013): Dr Who and Race. Bristol/Chicago, Intellect; Pnina werbner and Tariq Madood (2016): Debating Cultural Hybridity: Multi-Cultural Identities and the Politics oof Anti-Racism. London, 2nd Books

In order to see what is going on we need to engage a multidisciplinary intersectional analysis61. Hence we can define racism as a social construct of prejudice, discrimination, hostility and antagonism developed in the late 18th and 19th centuries by Europeans based on the hierarchical stratification of races and reinforced by the historical processes of colonialism, imperialism and the dynamic of White power and privilege. It operates on the assumption of White biological, cultural, economic and political racial superiority. It is also a social phenomenon that is dynamically constantly evolving and operating on individual, structural and institutional levels, constantly interacting with other social phenomena such as class, gender religion and ethnicity, being amoeba like, constantly changing form and substance and often creating new and hybrid manifestations unrecognised by the official legal system and western academics. It is a debilitating process which dehumanizes, marginalizes and dis-empowers and under-develops Black and other non White peoples and privileges White patriarchal western society. Racism is manifest in the daily everyday lived experiences of Black and other non White peoples. In a Bahamian context, as I have indicated elsewhere, it is essential that we be guided by historical specificity and deviating from traditional Western scholarship, essentialize and contextualize the daily lived experiences of ordinary everyday Caribbean peoples, taking full account of their plural and multicultural realities62. In this regard, Nettleford indicates that in their “self doubt and lack of confidence”, too many Caribbean people still tend to follow what the North Atlantic has done.63

61 Humanities at Stanford (2010): “Changing Perceptions of Race and Ethnicity” In Examining Conversations About Race With a Multidisciplinary Scope. Available Online <http://shc.stanford.edu/news/research/examining-conversations-about-race-multidisciplinary-scope>; Andrea Romei and Salvatore Ruggieri (2013): “A Multidisciplinary Survey of Discrimination Analysis” In The Knowledge Engineering Review Vol. 00:0, 1-54; Dean E. Mundy (2016): “Bridging the Divide: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of Diversity Research and the Implication for Public Relations” In Research Journal of the Institute of Public Relations, Vol.3(1) August. Available Online < https://prjournal.instituteforpr.org/wp- content/uploads/Dean-Mundy-1-1.pdf>; David R. Roediger and Donald M. Shaffer (eds.) (2016): The Construction of Whiteness: An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Race Formation and the Meaning of White identity. USA, University Press of Mississippi

62 Arthur Dion Hanna jr. (2013): Forging Critical Legal Analysis In Clinical Legal Education: A Multicultural Caribbean Perspective On Legal Education In The 21st Century. Paper Presented to the 2013 Law Schools' Teaching Effectiveness Conference: ‘Toward an Empirical Approach to Teaching Legal Education' Jamaica Pegasus Hotel, Kingston, March 22, 2013

63 Rex Nettleford, “Prologue: The Caribbean and Cultural Studies: More Than Grimace and Colour” In Brian Meeks (ed.) Culture, Politics, Race and Diaspora: The Thought of Stuart Hall. Kingston and London. Ian Randle and Lawrence and Wishart. (2007:7)

Further, as I have asserted, in the social, political, economic, spatial and cultural dimensions of the legal landscape of the Caribbean, a complex interaction between race, class and gender mandates that we conduct our analysis from a multidisciplinary frame of reference, centred on the lived experiences of ordinary, everyday Caribbean people.64 It has been indicated that n the 18th century, prior to the arrival of the loyalists, the Bahamas Islands was a closed society dominated by a White male minority, which was a “common practice in the English portion of the Western hemisphere”65. However, Johnson indicates that, economically, Free Black people and persons of colour could legally own personal and real property, including slaves, and engage in economic activities although they were barred from selling liquor and had restrictions placed on trading and planting66. However, the arrival of the Loyalists, particularly from East Florida drastically changed the racial dynamic. In this regard, it has been pointed out that the relatively high percentage of White people in the Bahamas, its proximity to the United States, with its segregation practices, and close cultural ties to the United States, along with a weak Black middle class, “made for more antagonistic race relations in the Bahamas”67. Further, Curry points out that, historically, the Bahamas presents a unique model of race relations, incorporating elements of both West Indian and Southern United States systems68. He indicates that:

“The West Indian model, institutionalized during slavery, created a tripartite system with a distinct middle class comprised of coloreds who operated as a buffer between the elite White class and the laboring black masses. The colored middle classes, although the progenitors of White and black sexual liaisons, were rejected by Whites due to their colour while envied by the enslaved because of their freedom. In The Bahamas, evidence of the tripartite racial model was seen in all aspects of the colonies social, economic and political spheres. Hence, in recreational and social activities, coloreds in The Bahamas emulated the White minority in order to distance themselves from the black masses and gain respectability or even acceptance by Whites”69.

64 Arthur Dion Hanna jr. (2013) supra.. C/F Philomena Essed, Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory. Amsterdam. Sage Publications. (1991); Arthur Dion Hanna Jr., The Two Faces of Justice: Racism in the English Criminal Justice System. Unpublished Masters Dissertation. University of London (1994); Sorry I Can't Come Out to Play: Report of the Mary Seacole Racial Harassment Project on Racial Harassment and Attacks on the St. Matthews Estate. Leicester, Leicestershire. Leicester Racial Equality Council and Mary Seacole Racial Harassment Project. (1994); The Bahamian Appeals Process: Fractured Neo Colonial Reflections of Imperial Justice and the Development of Caribbean Jurisprudence in the 21st Century. Paper Presented to the National Bar Association Mid-Winter Meeting. Sheraton Nassau Beach Resort, Nassau Bahamas, 14 February (2013)

65 Whittington Bernard Johnson (2000): Race Relations in the Bahamas 17884-1815: The Non-Violent Transformation From a Slave to a Free Society. Fayetteville, University of Arkansas Press

66 Ibid.

67 Gail Saunders (2007): “The Race Card and the Rise to Power of the Progressive Liberal Party in the Bahamas” In the Journal of Caribbean History, Vol 41 (1⁄2) January

68 Christopher Curry (2018) supra.

69 Ibid.

Palmer points out that these “refugees” from the Southern United States not only supported slavery but they also preferred to remain loyal to the United Kingdom. The racial divisions engendered by the presence of these 'loyalists” in those early years, laid the foundation for the social organization and stratification of contemporary Bahamian society.70 Under the race paradigm engendered by the Loyalists, Black slaves were virtually powerless and could be bought or sold at “the masters' discretion” and because of the rigid colour bar, Free Black people were restricted from full participation in the society and economy of the islands.71 The segregated spatial dimensions of the Bahamian racial paradigm defined the stratified nature of Bahamian society, which was quite evident in the Out Islands (Family Islands) of the Bahamas, where segregated communities were developed, with all White settlements in Spanish Wells, Man-O-War Cay and Abaco, all Black settlements in Long Cay, Rum Cay, Cat Island, Mayaguana and Andros, and

bi-racial settlements in Green Turtle Cay and Harbour Island.72

70 Catherine Palmer (1994): “Tourism and Colonialism: The Experience of the Bahamas” In Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 21 (4)

71 Dean W. Collinwood (1989 a): The Bahamas Between Worlds. Decatur, Illinois, White Sand Press; (1989b): “The Bahamas in Social Transition” In Dean W. Collinwood and Steve Dodge (eds.) Modern Bahamian Society, Parkersburg,IA, Caribbean Books; L. D. Powels (1996): Land of the Pink Pearl: Recollections on Life in the Bahamas. Nassau Bahamas, Media Pub

72 Christine Palmer (1994) supra.

Palmer indicates that slavery was widespread and all Black people, free or slave, were subject to discrimination and racial prejudice, even after emancipation in 1838.73 As pointed out by Collinwood and Dodge: “Though the Blacks were no longer slaves, they were effectively barred from important roles in the English colonial administration and from lucrative economic pursuits. The Blacks were denied full citizenship rights and were exploited by the White autocracy”.74

Despite the historical legacy of racial differentiation and prejudice and the ongoing spatial, economic and social dimensions of the race phenomenon, much of the modern popular discourse on race has been characterized by a propensity to deny the essence of the enduring legacy of race in Bahamian society. Such historical amnesia and cognitive dissonance is clearly demonstrated in comments made in a letter to the Editor in the Nassau Guardian when the writer stated that the history of the Progressive Liberal Party's perennial usage of the race card to woo Black Bahamian voters to the political party and that “since the 1950s have pitted Black Bahamians Against White Bahamians”75. Further, the writer asserts that an accusation that all White Bahamians are racist is the “oldest play from the playbook of the PLP”76 and that this helped to “unseat” the ruling UBP in January of 1967. He further asserts that it was used throughout the “lengthy reign” of the late Sir Lynden Pindling to “frighten Black Bahamians” away from the FNM which had amalgamated with elements of the disbanded UBP old guard. The anonymous writer writing under the pseudonym 'Whistle Blower' concludes that whatever racial issues 'plagued' the Bahamas during the 1950s and 1960s, they are virtually non-existent today in the 21st century77. Such sentiments fly in the face of the social realities engendered by the historical colonial oligarchical social pyramid of racial differentiation. It is myopic to assume that the attainment of majority political rule in 1967 in the Bahamas somehow became a panacea for magically ending the deeply rooted phenomenology of race or racism endemic to Bahamian society.

73 Ibid.

74 Dean W. Collinwood and Steve Dodge (es.) (1989): Modern Bahamian Society. Parkersburg, IA., Caribbean Books

75 Nassau Guardian, May 23, 2012

76 Ibid.

77 Ibid.

Further, the notion that Black people have become racists is misguided and betrays an absolute failure to comprehend the essence of race and racism explored in this paper. By definition, the Black Bahamian community can never be considered racists, given the power dynamic of the Bahamian racial paradigm, with 15% of the Bahamian population which is White, controlling 85% of national resources, with the majority of Black Bahamians being landless and disempowered.

Palmer points out that, during the middle part of the 20th century, the White so called Bay Street Boys, who controlled the Bahamas, were a clique of wealthy merchants and lawyers with shops or offices on Bay Street She indicates that years of colonial rule served to strengthen the control of the “White minority elite”, as the members of the “colonial administration” were elected from this group.78 Palmer concludes that the “privileged status” of the White population is aptly stated in the following comments of a Black Bahamian: “At certain times, the Black population couldn't go to certain places, specifically on Nassau, because it was off limits to them. I've heard this said by a lot of elderly people, that during the British rule, a lot of Whites took advantage in terms of 'getting' favours. If you were White you could get land, you could get a loan at the bank. That's how Whites

in this country really got their money, because of favours”79.

It is quite clear that, despite the White oligarchy losing its stranglehold on political power in 1967, they continued to hold a virtual monopoly control of Bahamian land and natural resources.80 As a result of the historical process of racial subjugation and exploitation in the colonial process, enforced by the oligarchical control of the Bahamian economy, Black Bahamians have been, in the main, excluded from the “historical, social and technical transformations” that were taking place in the rest of the World.81

78 Catherine Palmer (1994) supra.; C/f Michael Craton and Gail Saunders (1999): A History of the Bahamas. Waterloo, Ont., San Salvador Press; Gail Saunders (2017):Race and Class in the Colonial Bahamas. Gainesville, University Press of Florida

79 Ibid.

80 Arthur Dion Hanna Jr. (2011) Land and Freedom: One Bahamas and a Tale of Two Cities. Paper Presented to the Bahamas Historical Association, 7th April, Nassau, Bahamas. Available online <http://www.academia.edu/12349576/Lans-and_Freedon-Onr_Bahamas_and_a_Tale_of_Two_Cities>

81 Albert Memmi (1990): The Colonizer and the Colonized. London, Easthscan; Catherine Palmer (1994): supra.

Similar cognitive dissonance and historical amnesia is revealed in comments of Larry Smith when he argued that: “Not surprisingly, it took well over a generation for Bahamians of both races (and those in-between) to even begin to come to terms with the changes wrought in 1967. For Blacks, centuries of slavery, exclusion \and second class citizenship had given way overnight to supreme political power, whereas Whites had seen their peculiar vision of Bahamian crashed overnight”82. Smith further contends that, “unfortunately the recent commemoration of January10 as 'Majority Rule day' is little more than crass PLP posturing” and that as Sir Arthur Foulkes noted, Bahamians of “all political and racial groups contributed to the democratic achievement of 1967”.83 He contends that after decades of being berated, humiliated and sidelined for the “sins of the past”, most White Bahamians have:

“Quietly disengaged from society, a fact which Black Bahamians are, ironically, quick to exploit.....For us to believe that we can fuse together One Bahamas in 30 years is a pipe dream. Indeed only Black Bahamians want this, Whites do not. If White Bahamians make up less than 15% of the population but control 85% of the wealth, then obviously, Black Bahamians still feel that White is right and the lighter the better. That is the social psychology of racism in the Bahamas. It seems that despite the passage of time and the obvious transformation of our society to the point where Whites are almost irrelevant to the national debate, many still feel ittle has changed. In fact Guardian columnist, Nicolette Bethel, recently suggested that Black people have been brainwashed into believing that their experience is the same as the American experience”84.

Astonishingly, Larry Smith further contends that, as far as he knew, “there is no difference between Whites and Blacks in the Bahamas” in the ownership of private property and that racism, “as it exists today” is not a “major concern” compared to other factors that prevent economic development and the “creation of wealth”. Smith asserts that White Bahamians are not: